Insurance Clerk (taking personal particulars of prospective policy-holder). "And what is your profession, Sir?"

Artist. "Painter."

Clerk. "What sort of painter?"

Artist. "Splendid."

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol. 159, September 8th, 1920, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol. 159, September 8th, 1920 Author: Various Release Date: October 14, 2005 [EBook #16877] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH *** Produced by Jonathan Ingram, Keith Edkins and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

There are rumours of Prohibition in Scotland. We can only say that if Scotland goes dry it will also go South.

By an order of the Food Controller rice has been freed from all restrictions as regards use. This drastic attempt to stem the prevailing craze for matrimony has not come a moment too soon.

We suppose it is due to pressure of business, but the Spanish Cabinet has not resigned this week.

The Daily Mail is offering one hundred pounds for the best new hat for men. The cocked hat into which Mr. Smillie hopes to knock the country is, of course, excluded from the competition.

A horse at Chichester has been run down by a train. Asked how he came to catch up with the horse the driver said he just let her rip.

Despite the repeated reports of his resignation in the London papers, Mr. Davis, the American Ambassador to Britain, states that he does not intend to retire. This contempt for English newspapers will be justifiably resented.

Mrs. Lillian Russell, of Rockland, Mass., is reported to have offered to sell her husband for twenty thousand pounds. It is a great consolation to those of us who are husbands that they are fetching such high prices.

The road-menders in Oxford Street who went on strike have now resumed work. The discovery was made by a spectator who saw one of them move.

A contemporary reports the prospect of fair weather for another three weeks. It looks as if Mr. Smillie is going to have a fine day for it after all.

A New York message states that the congregation of a New Jersey church pelted the Rev. F.S. Kopfmann with eggs. This is disgraceful with eggs at their present price.

We have just heard of a Scotsman who has a pre-Geddes railway time-table for sale, present owner having no further use for it.

It is stated in scientific circles that the present weather is due to the Gulf Stream. This relieves Mr. Churchill of considerable responsibility.

"The length of a bee's sting," says Tit Bits, "is only one thirty-second of an inch." We are grateful for this information because when we are being stung we are always too busy to measure for ourselves.

Those who maintain that nothing good ever comes from Russia have suffered a nasty slap in the face. A news message states that the Bolshevists have invited Mr. Smillie to visit Petrograd.

"Horsehair coats have made their appearance," says The Outfitter. Surely this is nothing very new. We have often seen horses wearing them.

A man who stole the same fowls twice has been charged at Grimsby. He pleads that his bookkeeper omitted to enter them in the day-book the first time.

It is now being hinted in political circles that Mr. William Brace, M.P., has consented to bequeath his moustache to the nation.

Mr. Smillie was much heartened by the news from Lucerne that the Prime Minister had climbed down the Rigi in three hours.

As a result of the new rise in the price of petrol many of the middle-class have been compelled to turn down their automatic cigarette-lighters.

Although we may appear to be a little previous, we have it on good authority that Mr. Bottomley is already making arrangements to predict that the approaching coal-strike will end before Christmas.

The various attempts to swim or cycle across the Channel having proved unsuccessful, we hear that interest is again being revived in the proposed Channel Tunnel.

It is rumoured that Councillor Clark has recently purchased a large consignment of Government flannel, in order to provide adequate underclothing for mixed bathers.

A large quantity of rusty piano wire, says a news item, has been found in a valuable milch cow at Boston, Lines. There is hope that the "Tune the Cow Died of" may now be positively identified.

According to a sporting paper there is a great shortage of referees this season. The offer to receive any member of this profession into the ranks of the Royal Irish Constabulary without further qualifications is no doubt responsible for fifty per cent. of the loss, whilst fair wear and tear probably account for the remainder.

"It is high time," writes a correspondent in The Daily Mail, "that a clearly defined waist-line should be reintroduced into feminine dress." Others claim that as the neck-line is now worn round the waist the reintroduction of a waist-line elsewhere can only lead to confusion.

Insurance Clerk (taking personal particulars of prospective policy-holder). "And what is your profession, Sir?"

Artist. "Painter."

Clerk. "What sort of painter?"

Artist. "Splendid."

"The part of the public is to keep cool."—The Times.

A strike should make this fairly easy.

From the advertisement of a "Unique Battlefields Tour":—

"Passports and Visors obtained and annoyances reduced to a minimum."—Daily Paper.

Then why this knightly precaution?

We all knew at the office that Micklebrown had gone to Cocklesea for his holiday. If anyone had offered him a free pass to the Italian lakes or any other delectable spot Micklebrown would have declined it and taken his third return to Cocklesea. Like Sir Walter Raleigh when he started for South America to find a gold-mine, Micklebrown had an object in view. He hoped to discover a topaz in Cocklesea. We knew the reason for this optimism. We had been shown the lizard-brooch, a dazzling thing of gold and precious stones, which Micklebrown had picked up last Bank Holiday on the cliff at Cocklesea and presented to his fianc?e, Miss Twitter, after inquiry at the police-station had failed to discover its owner.

Most people would have been satisfied to leave well alone, but Micklebrown is a man who hankers after the little more. The lizard's tail was composed of topaz stones, and from its tip one topaz was obviously missing. "My firm impression is that I did the damage when I trod on it," Micklebrown said. "You see I put my foot right slap on the thing. I can't get it out of my head that that topaz stuck in the mud and it's sticking there to this day. Anyway I go to Cocklesea for my holiday to look. I know the very identical spot." He closed his eyes the better to visualize it. "You go up a little path behind the mixed-bathing boxes, turn sharp to the right at the top of the cliff, past two pine-trees and a clump of gorse, go a trifle inland through a lot of thistles until you come on three blackberry bushes; the topaz should be ten inches south-west of the middle one."

"The colour'll be a bit washed out, won't it?" young Lister said; "we've had a lot of rain since Bank Holiday."

Micklebrown's lip curled but he said nothing. Only to us, his intimates, did he confide that he had no expectation of finding the topaz on the surface; he expected to search through several strata of mud, and he was taking a magnifying-glass and a gravy-strainer with him.

We heard nothing further until I had a postcard from him saying that the rain had caused the blackberries so to multiply that he found it impossible to identify the particular bush near which he had stepped on the lizard; he was therefore making a general search over the area. After that we followed the tale in The Daily Trail:—

Seaside Visitor's Strange Conduct.

Much curiosity has been aroused at Cocklesea by the behaviour of a visitor who spends his days on the cliff burrowing in the earth in all weathers. Speculation is rife as to the object of his occupation. It is generally concluded that he is the victim of shell-shock.

Romantic Disclosure by Cocklesea Cliff Burrower.

In conversation with our representative yesterday Mr. Micklebrown, whose burrowing on the cliff at Cocklesea has been observed with such interest, indignantly denied the imputation of shell-shock. Mr. Micklebrown, it appears, is spending his vacation at Cocklesea in the hope of recovering a topaz which formed part of a valuable piece of jewellery which he had the good fortune to pick up on the cliff on Bank Holiday. Being anxious to notify his discovery without delay to the police (who however failed to trace the owner) and being bound to catch the return steamer, Mr. Micklebrown had no opportunity to prosecute a search at the time. He therefore determined to visit Cocklesea again at the earliest opportunity to do so.

In the meanwhile Miss Rosalind Twitter, Mr. Micklebrown's fianc?e, is the happy possessor of the ornament. Interviewed by a correspondent, Miss Twitter, a winsome dark-eyed brunette in a cretonne chemise frock, said, "Yes, it is quite true that I sleep with it under my pillow. I hope Dinky (Rosalind's pet name for her lover) will find the topaz; he is a dear painstaking boy. I have never had such a lovely piece of jewellery in my life and I am going to be married in it." (Photo of Miss Twitter on back page. Inset (1) The brooch; (2) Mr. Micklebrown.)

Search for Missing Topaz at Cocklesea.

Owing to the publicity given to his story by The Daily Trail hundreds of willing hands assisted Mr. Micklebrown in his search yesterday. Pickaxes, shovels and wooden spades were being freely wielded on the cliff. Miss Twitter writes to us: "Every moment I expect a telegram from Dinky that the topaz is found. I can never be grateful enough to The Daily Trail for the interest it has taken in my brooch."

Dramatic Sequel To Search For Cocklesea Topaz.

As a result of the wide circulation of The Daily Trail the brooch picked up by Mr. Micklebrown on the cliff on Bank Holiday has been claimed by Miss Ivy Peckaby, of Wimbledon. Miss Peckaby identified the brooch from the photograph which appeared in our issue of Friday. Conversing with our representative, Miss Peckaby, a slim, golden-haired girl in hand-knitted cerise jumper with cream collar and cuffs, said, "I jumped for joy when I recognised my darling brooch on your picture page. I must have lost it at Cocklesea on Bank Holiday, but I didn't miss it until two Sundays afterwards. I shall never forget what I owe to The Daily Trail."

Questioned as to the missing topaz Miss Peckaby sighed. "It has always been missing," she said. "You see, Clarence" (Miss Peckaby's affianced husband) "bought the brooch second-hand; he is going to have another topaz put in when he can afford it; but topazes are so dreadfully dear." (Photo of Miss Peckaby recognising her brooch on the back page of The Daily Trail.)

Last Chapter in Cocklesea Romance.

Free Gift of a Topaz by The Daily Trail.

Yesterday Miss Ivy Peckaby was the happy recipient of a topaz at the hands of a representative of The Daily Trail. The stone, which is of magnificent colour and quality, is the free gift of The Daily Trail. The Daily Trail is also defraying the entire cost of setting the gem in Miss Peckaby's brooch. Photo on back page of Miss Peckaby acknowledging The Daily Trail's free gift of a topaz. Inset: The topaz.)

I have heard nothing further from Micklebrown.

Many birds there be that bards delight in;

I to one my tribute verse would bring;

Patience, reader! no, it's not the nightin-

gale I'm going to sing.

Sweet to lie at ease and for a while hark

To a "spirit that was never bird;"

Still I don't propose to sing the skylark,

As perhaps inferred.

I'm content to leave it to a fitter

Tongue than mine to hymn the "moan of doves,"

Or the swallow, apt to "cheep and twitter

Twenty million loves."

I'm intrigued by no precocious rook, who

Haunts the high hall garden calling "Maud;"

Mine's no "blithe newcomer" like the cuckoo

Wordsworth used to laud.

Never could the blackbird or the throstle

(From the poet each has had his due)

Win from me such perfectly colossal

Gratitude as you.

You, I mean, accommodating partridge,

By some lucky chance (the only one,

Spite of much expenditure of cartridge)

Fallen to my gun.

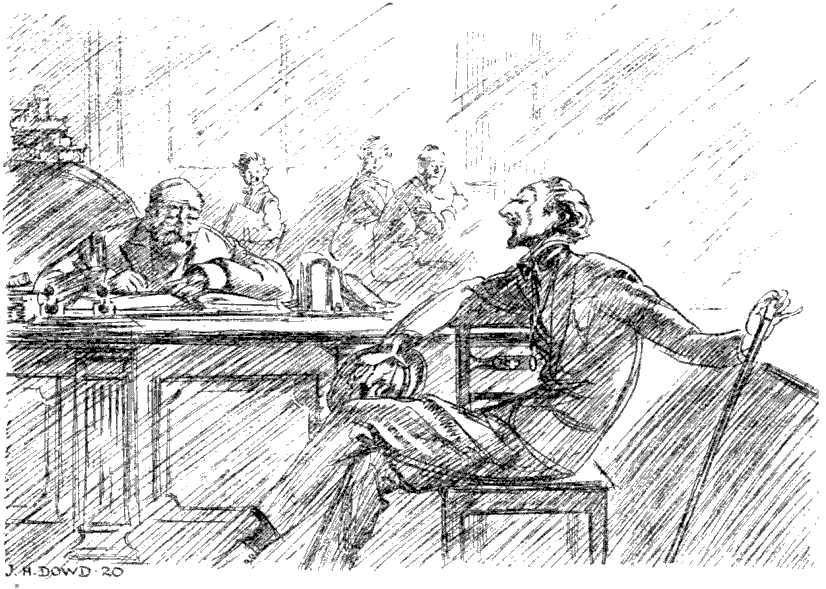

War Veteran. "THEY TOLD ME I WAS FIGHTING FOR DEAR LIFE, BUT I NEVER DREAMT IT WAS GOING TO BE AS DEAR AS ALL THIS."

Father. "Oh, yes, I used to play quite a lot of cricket. I once made forty-seven."

Son. "What—with a hard ball, Father?"

The idea and the name for it were the invention of the ingenious Piggott. I am his first initiate, and with the zeal of the neophyte I am endeavouring to make his discovery more widely known. The game, which is healthy and invigorating, can be carried on in any of the remoter suburbs, where the train-service is not too frequent. All that is required is a fairly long and fairly straight piece of road, terminating in a railway-station, and a sufficiency of City men of suitable age and rotundity.

The scheme is based on the Herd instinct—on the tendency of most creatures to follow their leader. For example, if you are walking down to your early train, with plenty of time to spare as you suppose, and you observe the man in front of you looking at his watch and suddenly quickening his steps, first to a smart walk, then to a brisk jog-trot, it is not in human nature, however you may trust your own watch, not to follow suit. This is precisely what Piggott led me to do one morning about six weeks back.

When, on reaching the station ten minutes too early, I remonstrated with him, he apologised.

"I am sorry," he said; "I didn't know you were behind me. I was really pace-making for 'Flyaway'—there, over there." And Piggott pointed to a stoutish man with iron-grey whiskers mopping his forehead and the inside of his hat, and looking incredulously at the booking-hall clock.

"But that is Mr. Bludyer, senior partner in Bludyer, Spinnaway & Jevons," I said.

"It may be," replied Piggott. "But I call him Flyaway. I find it more convenient to have a stable-name for each of my racers." And he proceeded to expound his invention to me.

Like so many great inventors he had stumbled upon the idea by chance one morning when his watch happened to be wrong; but he had developed the inspiration with consummate art and skill. It became his diversion, by means of the pantomime that had so successfully deceived me—by dramatically shooting out his wrist, consulting his watch, instantly stepping out and presently breaking into a run—to induce any gentleman behind him who had reached an age when the fear of missing trains has become an obsession to accelerate his progress.

"It is amazing," he said, "how many knots you can get out of the veriest old tubs. This morning, for instance, Flyaway has taken only a little over six minutes to cover seven furlongs. That's the best I have got out of him so far, but I hope to do better with some of the others."

"You keep more than one in training?" I questioned.

"Several. If you like I will hand some over to you. Or, better still," he added, "you might prefer to start a stable of your own. That would introduce an element of competition. What about it?"

I accepted with alacrity. The very next day I made a start, and within a week I had a team of my own in training. The walk to the station, which formerly had been the blackest hour of the twenty-four, I now looked forward to with the liveliest impatience. Every morning saw me early on the road, ready to loiter until I found in my wake some merchant sedately making his way stationwards to whom I could set the pace. I always took care, however, not to race the same one too frequently [pg 185] or at too regular intervals, and I take occasion to impress this caution on beginners.

In the train on the way to the City Piggott and I would compare notes, carefully recording distances and times, and scoring points in my favour or his. It would have been better perhaps had we contented ourselves with this modest programme. Others will take warning from what befell. But with the ambition of inexperience I suggested we should race two competitors one against the other, and Piggott let himself be overpersuaded.

I entered my "Speedwell," a prominent stockjobber. Handicapped by the frame of a Falstaff, he happily harbours within his girth a susceptibility to panic, which, when appropriately stimulated, more than compensates for his excess of bulk. The distance fixed was from the Green Man to the station, a five-furlong scamper; the start to be by mutual consent.

Immediately on our interchange of signals I got my nominee in motion. This is one of Speedwell's best points: he responds instantly to the least sign, to the slightest touch of the spur, so to speak. Another is staying power. Before we had gone fifty yards I had got him into an ungainly amble, which he can keep up indefinitely. Though never rapid, it devours the ground.

Piggott was not so lucky. At the last minute he substituted for the more reliable Flyaway his Tiny Tim, a dapper little solicitor, not more than sixty, who to the timorousness of the hare unites some of her speed. In fact, in his excess of terror he sometimes runs himself to a standstill before the completion of the course. He suffers, moreover, from short sight and in consequence is a notoriously bad starter. On the morning in question he failed for several minutes to observe Piggott's pantomime, and Speedwell had almost traversed half the distance while Tiny Tim still lingered in the vicinity of the starting post. Only by the most exaggerated gestures did Piggott get him off. Once going, however, he took the bit in his teeth and went like the wind. Soon I caught the pit-pat of his footfall approaching. I pulled Speedwell together for a supreme effort. But there were still two hundred yards to cover as his rival drew abreast. A terrific race ensued. Scared at the spectacle of the other's alarm, each redoubled his exertions. Neck and neck they ran. Could Tiny Tim last? Had he shot his bolt? Could Speedwell wear him down?

Unfortunately the question was never settled. As they raced they overtook a group of business men, youngsters of forty or so, untried colts that had never yet been run by Piggott or me. These suddenly took fright and bolted. Inextricably mingled with our pair the whole lot stampeded like a herd of mustangs. The station approach scintillated with the flashing of spats as the Field breasted the rise. It was a grand sight, though so many fouls occurred that it was obvious the race was off. But things became serious when the entire crowd attempted to pass simultaneously through the booking-hall doors. Speedwell sprained a pastern and Tiny Tim sustained a severe kick on the fetlock. Both will require a fortnight's rest before they can be raced again.

This will be a warning to us and to others too, I hope. Still, it will not deter us from racing in the future. Nor should it deter others, for the sport is a glorious one and I hope it may become universal in the outer suburbs. Piggott and I will be only too glad to give advice or any other assistance that lies in our power to those who contemplate starting local clubs in and around London.

Old Dame (to visitor who has been condoling with her on a recent misfortune). "Och, I'm gey ill. I've been cryin' sin' fower this mornin', an' I'm just gaun tae start agen as soon's I've sippit this bicker o' parritch."

All day long I had been possessed by that odd feeling that comes over one unaccountably at times, as of things being a little strange, interesting—somehow different, so that I was not at all surprised to find the Fairy Queen waiting for me when I entered my flat.

It was a warm evening and she sat perched on the tassel of the blind, lightly swaying to and fro in the tiny breeze that came dancing softly over the house-tops.

I saw her at once—one is always aware of the presence of the Fairy Queen.

I made my very best curtsey and she acknowledged it a little absent-mindedly.

"I want your advice this time," she said.

I smiled and shook my head deprecatingly.

"But how ...?" I began.

"It's about Margery and Max," she continued.

I was much astonished.

"Margery and Max," I echoed slowly. "But surely there's no need to trouble about them. It's a most delightful engagement. They're blissfully happy. I saw Margery only yesterday ..."

"Oh, the engagement's all right," said the Queen. "As a matter of fact it was I who really arranged that affair. Of course they think they did it themselves—people always do—but it would never have come off without me. No, the trouble is I don't know what to give them for a wedding present. You see I'm particularly fond of Margery; I've always taken a great interest in her, and I do want them to have something they'll really like. But it's so difficult. They have all the essential things already: youth, health, good fortune, love of course; and I can't go giving them motor-cars and grandfather clocks and unimportant things of that kind. Now can I?"

I agreed. As it happened I was in a somewhat similar predicament myself, though from rather different causes.

"Can't you think of anything?" she asked a little petulantly, evidently annoyed at my inadequacy. I shook my head.

"I can't," I said. "But why not find out from them? It's often done. You might ask Margery what Max would like and then sound him about her."

The Queen brightened up. "What a good idea!" she said. "I'll go at once." She's very impulsive.

She was back again in half-an-hour, looking pleased and excited. Her cheeks were like pink rose-leaves.

"It's all right about Max," she said breathlessly. "Margery says the only thing he wants frightfully badly is a really smashing service. He's rather bothered about his. So I shall order one for him at once. I'm very pleased; it seems such a suitable thing for a wedding present. People often give services, don't they? And now I'll go and find Max." And she was off before I could utter a sound.

But this time when she returned it was evident that she had been less successful.

"It's absurd," she said, "perfectly absurd!" She stamped her foot, and yet she was smiling a little. "I told him I would bestow upon Margery anything he could possibly think of that she lacked. That any quality of mind or heart, any beauty, any charm that a girl could desire, should be hers as a gift. I assured him that there was nothing I could not and would not do for her. And what do you think? He listened quite attentively and politely—oh, Max has nice manners—and then he looked me straight in the eyes and 'Thank you very much,' he said; 'it's most awfully kind of you. I hope you won't think me ungrateful, but I'm afraid I can't help you at all. There's nothing—nothing. Margery—well, you see, Margery's perfect.' I was so annoyed with him that I came away without saying another word. And now I'm no further than I was before as regards Margery. Mortals really are very stupid. It's most vexing."

She paused a minute, then suddenly she looked up and flashed a smile at me. "All the same it was rather darling of him, wasn't it?" she said.

I nodded. "I wonder ...," I began.

"Yes?" interjected the Queen eagerly.

"... I wonder whether you could give her that, just that for always?"

"What do you mean?" said the Queen.

"I mean," I said slowly, "the gift of remaining perfect for ever in his eyes."

The Queen looked at me thoughtfully. "He'll think I'm not giving her anything," she objected.

"Never mind," I said, "she'll know."

The Queen nodded. "Yes," she said meditatively, "rather nice—rather nice. Thank you very much. I'll think about it. Good-bye." She was gone.

"On Monday evening an employee of the —— Railway Loco. Department dislocated his jaw while yawning."—Local Paper.

It is expected that the company will disclaim liability for the accident, on the ground that he was yawning in his own time.

The Centipede.

The centipede is not quite nice;

He lives in idleness and vice;

He has a hundred legs;

He also has a hundred wives,

And each of these, if she survives,

Has just a hundred eggs;

And that's the reason if you pick

Up any boulder, stone or brick

You nearly always find

A swarm of centipedes concealed;

They scatter far across the field,

But one remains behind.

And you may reckon then, my son,

That not alone that luckless one

Lies pitiful and torn,

But millions more of either sex—

100 multiplied by x—

Will never now be born.

I daresay it will make you sick,

But so does all Arithmetic.

The gardener says, I ought to add,

The centipede is not so bad;

He rather likes the brutes.

The millipede is what he loathes;

He uses fierce bucolic oaths

Because it eats his roots;

And every gardener is agreed

That, if you see a centipede

Conversing with a milli—,

On one of them you drop a stone,

The other one you leave alone—

I think that's rather silly.

They may be right, but what I say

Is, "Can one stand about all day

And count the creature's legs?"

It has too many, any way,

And any moment it may lay

Another hundred eggs;

So if I see a thing like this1

I murmur, "Without prejudice,"

And knock it on the head;

And if I see a thing like that2

I take a brick and squash it flat;

In either case it's dead.

A.P.H.

(1) and (2). There ought to be two pictures here, one with a hundred legs and the other with about a thousand. I have tried several artists, but most of them couldn't even get a hundred on to the page, and those who did always had more legs on one side than the other, which is quite wrong. So I have had to dispense with the pictures.

"Ainsi parla l'?diteur du Daily Herald. Lord Lansbury a toujours ?t? l'enfant ch?ri et terrible du parti travailliste anglais."—Gazette de Lausanne.

"Wanted.

Small nicely furnished house, nice locality, for nearly married couple, from August 1st."—Johannesburg Star.

We trust that no one encouraged them with accommodation.

Mary settled her shoulders against the mantel-piece, slid her hands into her pockets and looked down at her mother with faint apprehension in her eyes.

"I want," she remarked, "to go to London."

Mrs. Martin rustled the newspaper uneasily to an accompanying glitter of diamond rings. Mary's direct action slightly discomposed her, but she replied amiably. "Well, dear, your Aunt Laura has just asked you to Wimbledon for a fortnight in the Autumn."

Mary did not move. "I want," she continued abstractedly, "to live in London."

Mrs. Martin glanced up at her daughter as if discrediting the authorship of this remark. "I don't know what you are thinking of, child," she said tartly, "but you appear to me to be talking nonsense. Your father and I have no idea of leaving Mudford at present."

"I want," Mary went on in the even tone of one hypnotised by a foregone conclusion, "to go and live with Jennifer and write—things."

Mrs. Martin's gesture as she rose expressed as much horror as was consistent with majesty.

"My dear Mary," she said coldly, "let me dispose of your outrageous suggestion before it goes any further. You appear to imagine that because you have been earning a couple of hundred a year in the Air Force during the War you are still of independent means. Allow me to remind you that you are not. Also that your father and I are unable and unwilling to bear the expenses of two establishments. Please consider the matter closed."

She swept from the room. Mary whistled softly to herself, then she walked to the desk and wrote a letter.

"... And that's that," she finished. "So now to business. I will send you some articles at the end of the week, and for goodness' sake be quick, because I can't stand this much longer."

When she had posted it she retired to her room and was no more seen till dinner.

They were bright articles and, like measle-spots, they appeared rapidly after ten days or a fortnight; unlike measles they seemed to be permanent. They dealt irreverently with Mudford society, draped in a thin veil of some alias material, and they signed themselves "Blight."

"Disgraceful!" snorted Colonel Martin, throwing one crumpled newspaper after another into the waste-paper basket. "Ought to be publicly burned! As if it weren't enough to find the beastly things all over the Club, without being pestered with them at home, making fun of the best people in Mudford. Bolshevism! Fellow ought to be shot! Wish I knew who he was and I'd do it myself. I will not have another word of this poisonous stuff in my house. D'you hear, Gertrude?"

Mrs. Martin trailed into the hall in search of her sunshade.

"It's so difficult," she complained en route, "to know what paper he's coming out in next and stop it in time;" and she wandered mournfully into the garden.

"Mary," she sighed, sinking into a chair on the lawn, "have you noticed anything peculiar in the way people speak to us lately? Of course it may be only my imagination, and yet," she hesitated, "Admiral and Lady Rogers were quite—quite formal to me yesterday."

Mary balanced her tennis racquet on her outstretched hand and laughed. "It's the local Blight, I suppose. You and Father are about the only people left who haven't been withered yet, and the others are bound to think there's something suspicious about you. Stupid of me—I didn't think of that. I'm sorry."

Her mother started. "What do you mean?" she inquired sharply.

Mary rose languidly. "However," she added graciously, "I will put that right for you next week. I have several sketches that will do."

Mrs. Martin's face registered inquiry, incredulity, indignation and apoplexy in chronological order; then the garden gate clicked and a young man walked across the lawn. Mary looked down at her mother and spoke quietly.

"I think it is time you knew that I wrote those articles. One writes about what one sees, and as long as I remain here I shall see Mudford."

"Pardon me," began the young man, arriving, "but is this Colonel Martin's house?"

Mrs. Martin made no effort to reply and Mary reassured him.

"It's like this," he continued frankly. "I'm representing The Daily Rebel, and I'm awfully anxious to get certain information for my paper. I was speaking to Admiral Rogers just now and he told me I should probably get it here if I tried. He said he could only give me a guess himself and I had better come to headquarters. Madam," he bowed towards Mrs. Martin, "will you kindly tell me if you are the famous ..."

Here Mary interposed. "My mother," she said serenely, "is not the Mudford Blight. Nor is my father."

The young man wheeled on her.

"Then you ...?" he queried.

Mary hesitated, questioning her mother with a glance.

"My daughter," replied Mrs. Martin in a strangled voice, "cannot possibly be the person you seek since she is not a Mudford resident. She lives in London and is only staying here till to-morrow—at the latest."

Mary smiled radiantly and sent a wire later in the afternoon.

Young Miner's Mother. "I can't do nothink wiv our 'Erbert since 'e voted for the strike. Wen I ask 'im to run a errand 'e says it isn't a man's job."

"While crossing a field near Berwick a gamekeeper noticed a dear coming in his direction and he took cover in a hayrick."—Scotch Paper.

"Parlourmaid Wanted, afternoons, 2-6.30, galvanised iron, 50 ft. to 140 ft. long x 21 ft."—Local Paper.

It needs a girl with an iron constitution to support such a frame.

"For Sale, Clergyman's Grey Costume, latest style; also Jumper, never worn."—Irish Paper.

The reverend gentleman appears to have jibbed at the jumper.

Village Umpire (advancing down pitch, after resisting two appeals for l.b.w.). "You better take a fresh middle, Jarge, 'cos if 'e 'its 'ee again in the zame place I shall 'ave to give 'ee out."

Dear Mr. Punch,—I have been spending my holiday at a watering place, a place that fully deserves its epithet. My London daily has been my only entertainment, and towards the evening hours I have found myself wandering about the less familiar beats of it. I have become an intimate of the City Editor, and I hasten to inform you, Mr. Punch, that he has introduced me to a side of the Gay Life which I have been missing all these years. I will set out the tale of it, even at the risk of making your readers blush.

It appears that recently a feeling spread in the Market (and that all these goings-on should take place in a market adds, in my view, to their curiousness) that a crisis had been reached in monetary restrictions and things might be eased a bit. Apparently there is a circle of people in the know, and by them it was immediately appreciated what this "relaxation" implied. The first overt sign of something doing was a "heavy demand for money," a need which I too, for all my quiet domesticity, have felt from time to time. No doubt the fast City set were filling their pockets before commencing a course of "relaxation." The next development was that the Market was approached from all sides with "applications for accommodation." I can picture the merry parties rolling up in their thousands, booking every available house, flat or room, and even paying very fancy prices for the hire of a booth for a house-party.

It may give you some idea of the nature of their "relaxation" when I say that our old friend the Bank of England seems to have so far forgotten herself as to start making advances to the Government. My City Editor, who is possibly a family man, cannot bring himself to give details; he just states the fact, merely adding the significant comment that "the usual reserve of the Bank is rapidly disappearing." The effect of this example is appearing in the most respectable quarters. "All attempts are now failing," he reports, for example, "to keep the Fiduciary Issue within limits." Reluctantly he mentions a "considerably freer tendency in Discount circles."

Further he records a tendency to over-indulgence in feasting. I read of figures (I hardly like to quote this bit) becoming "improperly inflated." Will you believe me when I add that a section of those participating in the beano, whose one fear was, apparently, that it would all end only too soon, actually were heard expressing the apprehension, to quote verbatim, "that they would deflate too rapidly." "The whole tone of the Market," says my City Editor, "became distinctly cheerful," and he pauses to comment on the one redeeming feature: "War Loan remaining steady, 84-15/16 middle."

And thence to the shocking climax: Trade Returns were unable to balance properly, and Money (to be absolutely outspoken and no longer to mince matters) got tight.

After this I was not surprised to read of "Mexican Eagles rising on the announcement of the new Gusher." Nor a little later to find the announcement, "Stock Exchange Dull." A very natural reaction.

Yours ever,

Extract from a plumber's account:—

"To making good leaks in pipes, 8/6."

"Wanted 2 Lions male and female or either any of them. What will be the cost? Where they can be had and when can we get."—Indian Paper.

Can any of our readers oblige this eager zoologist?

"An incident of an extraordinary nature befell Colonel ——, C.B., while playing a golf match at Brancaster. A large grey cow swooped down, picked up his ball and flew away with it."—Newfoundland Paper.

Probably a descendant of the one who jumped over the moon.

Betty. "Mummy, how did these two marks get on my arm?"

Mother. "The doctor made them. They're vaccination marks. There ought properly to be four of them."

Betty (after much deliberation). "Mummy, did you pay for four?"

When I consulted people about my nasal catarrh, "There is only one thing to do," they said. "Run down to Brighton for a day or two."

So I started running and got as far as Victoria. There I was informed that it was quite unnecessary to run all the way to Brighton. People walked to Brighton, yes; or hopped to Kent; but they never ran. The fastest time to Brighton by foot was about eight hours, but this was done without an overcoat or suit-case. Even on Saturdays they said it was quicker to take the train than to walk or to hop.

Brighton has sometimes been called London by the Sea or the Queen of Watering Places, but in buying a ticket it is better to say simply Brighton, at the same time stating whether you wish to stay there indefinitely or to be repatriated at an early date. I once asked a booking-clerk for two sun spots of the Western coast, and he told me that the refreshment-room was further on. But I digress.

One of the incidental difficulties in running down to Brighton is that the rear end of the train queue often gets mixed up with the rear end of the tram queue for the Surrey cricket ground, so that strangers to the complexities of London traffic who happen to get firmly wedged in sometimes find themselves landed without warning at the "Hoval" instead of at Hove. To avoid this accident you should keep the right shoulder well down and hold the shrimping-net high in the air with the left hand. If you do get into the train the best place is one with your back to the window, for, though you miss the view, after all no one else sees it either, and you do get something firm to lean up against. It was while I was travelling to Brighton in this manner that I discovered how much more warm this summer really is than many writers have made out.

Around Brighton itself a lot of legends have crystallized, some more or less true, others grossly exaggerated. There is an idea, for instance, that all the inhabitants of this town or, at any rate, all the visitors who frequent it, are exceedingly smart in their dress. Almost the first man whom I met in Brighton was wearing plus 4 breeches and a bowler hat. It is possible, of course, that this is the correct costume for walking to Brighton in. Later on I saw a man wearing a motor mask and goggles and a blue-and-red bathing suit. Neither of these two styles is smart as the word is understood in the West End.

Then there is the story that prices, especially the prices of food, are exceedingly high in Brighton. After all, the cost of food depends everywhere very much upon what you eat. I see no reason for supposing that the price of whelks in Brighton compares unfavourably with the price of whelks in other great whelk-eating centres; but the price of fruit is undeniably high. I saw some very large light-green grapes in a shop window, grown, I suppose, over blast furnaces, and when I asked what they cost I was considerably surprised. Being afraid, however, to go out of the shop without making a purchase, I eventually bought one.

But these things are all by the way. It was when I reached the sea-front at Brighton that I made the tremendous discovery which is really the subject of this article. I realised the secret of Brighton's charm. It can be stated very simply. It lies in the number of things one needn't do there.

At little seaside resorts, such as Cockleham, there are a very limited number of things that people do, and as soon as one gets to Cockleham an irresistible inclination seizes one not to do them to-day. If anybody says it is a good day for bathing you say it is better for boating. And if they agree you wonder if, after all, golf.... And so you preserve your independence and feel rested and stave off for a little while the evil day. But only for a little. Very soon, for lack of alternative suggestions, you are bound to be dragged in and do something.

But at Brighton the number of things to do is so enormous and so varied that you can spend days and days in not doing them. On the pier alone there are something like a hundred complicated automatic machines which you needn't work; there are fishing-rods which you needn't hire, and concerts to which you needn't listen. The sea is full of rowing boats and motor-launches which you needn't charter, and the land is full of motor-brakes which you needn't board. You needn't mixed-bathe nor go and watch the professional divers, nor the fish in the Aquarium, nor the people with Norman profiles arriving in motor-cars at the hugest hotels. You can simply sit still on the beach and discuss which of these exciting things you won't do first. And while you sit still on the beach you can throw pebbles into the sea. No one has ever thrown as many pebbles into the sea in his life as he wanted to, because someone keeps saying, "Well, you must decide;" but at Brighton you can throw more than in any seaside place that I know. And, now I come to think of it, I wonder that there is no charge for throwing pebbles into the sea at Brighton. I should have thought a low wall with turnstile gates and three or four shies a penny ... but I leave this commercial idea for the Town Council to work out.

When I had thrown a great many pebbles into the sea I began to nerve myself for the struggle of returning. Over that struggle I prefer, as the saying is, to draw a veil. Suffice it to say that it is harder to run up to Brighton than it is to run down. But whilst I was running up I made a curious and interesting discovery. I found that the spell of Brighton had cured my cold. I had lost it in the soothing excitement of wondering what not to do next. This is the true panacea.

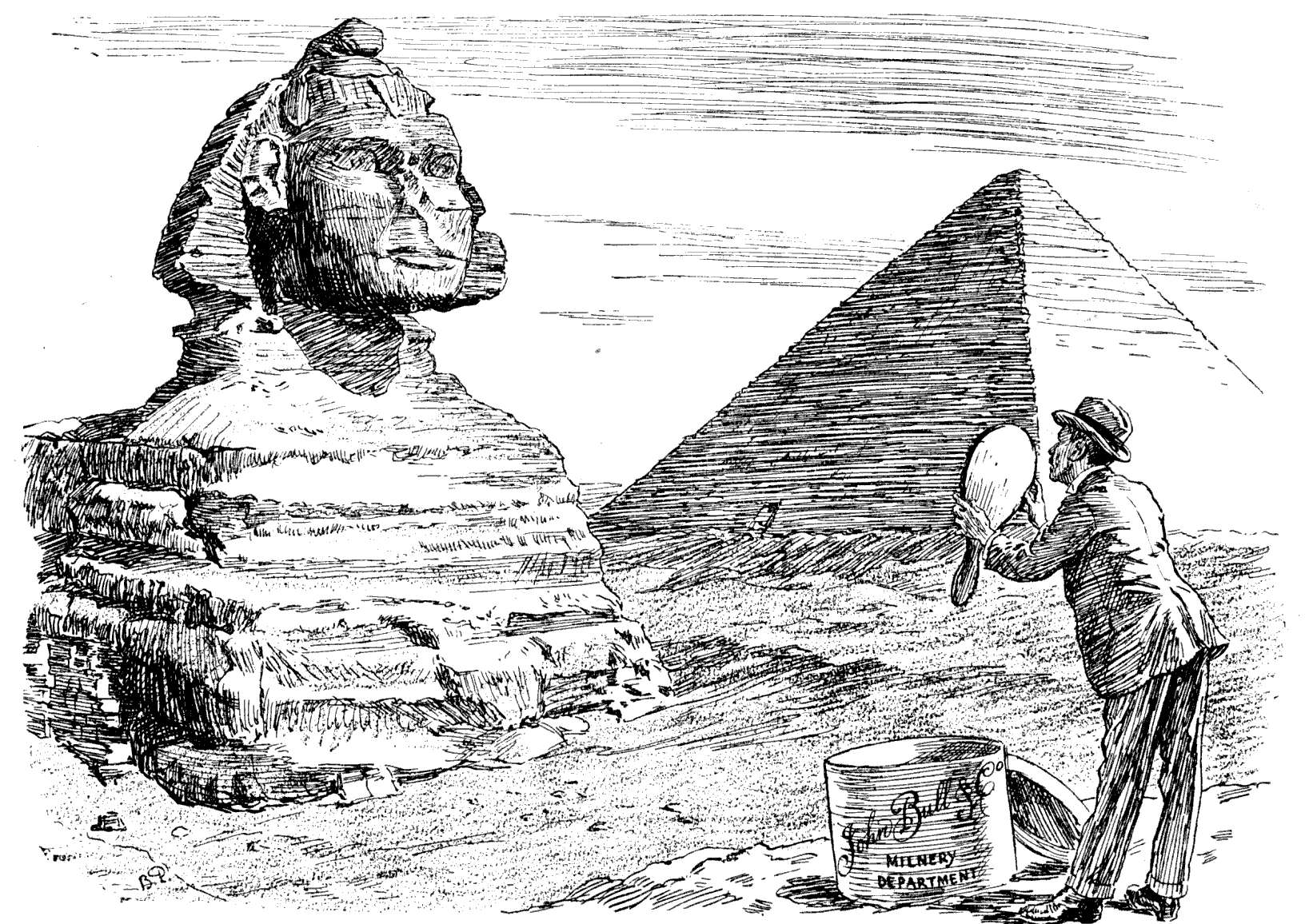

Egyptian Sphinx. "HOW DOES IT SUIT MY STYLE?"

The Lord High Milner. "WELL, I MAY BE PREJUDICED IN FAVOUR OF MY OWN CREATION, BUT I THINK IT MOST BECOMING."

The story has been told to you

Of good Adolphus Minns of Kew,

Whose virtuous ways have won renown

From Barking Creek to Acton Town.

Now with that hero's blameless life

Contrast the conduct of his wife:

Avoidance of egregious sins

Is not the way of Mrs. Minns.

That lady, I regret to say,

While bent on shopping every day,

Makes no attempt to get it o'er

Between the hours of ten and four.

To harassed booking-office clerks

She makes irrelevant remarks,

And tenders, to the crowd's despair,

A pound-note for a penny fare,

Or, what perhaps is even worse,

Starts fumbling in a baggy purse.

She'll step aboard a Highgate train,

Then check and double back again,

And ask a dislocated queue

If she is right for Waterloo.

The liftmen, who, you recollect,

Spoke of Adolphus with respect,

Are pessimistic, even for them,

About the fate of Mrs. M.

Where Gertrude Minns will go when she

Departs this life is not for me,

Or you, or liftmen, to decree.

And, any way, we needn't fret;

She shows no sign of dying yet.

Examiner. "What measures would you take if you had to treat a case of sunstroke?"

Boy Scout (who has negotiated fairly successfully a fractured jaw, broken forearm and severed femoral artery). "I would drag him into the shade, strip him to the waist, pour cold water on him and put him into isolation if there was any ice."

The letters of the alphabet were talking.

"It's been a wonderful season," said S. "I 'm very proud of it."

"Yes," said C; "I don't suppose so much interest was ever taken in cricket before. The number of people able to spend time at a match has been the greatest ever known."

L agreed. "Even on the middle days of the week," he said, "Lord's has been packed."

"Lord's, forsooth!" O struck in. "Lord's has been empty compared with the Oval. The Ovalites have lost no opportunity of watching their heroes."

"When you say 'their heroes' you mean also mine," said H. "But they are not confined to the Oval. I have some at Lord's too; in fact, all over the country. It has been, all the best critics say, an H year." He ticked them off on his fingers. "For Surrey, Hobbs and Hitch; for Middlesex, Hendren and Hearne; for Yorkshire, Hirst and Holmes; for Notts, Hardstaff; for Kent, Hardinge and Hubble; for Worcestershire, Howell. And four of them," he added, "are going to play for England in Australia. It's a feather in my cap, I can tell you," H went on. "And I needed the encouragement too. No one is treated so badly as I am, especially in London, where I'm being dropped all day long or forced into company which I don't care about. Isn't that true?"

"Not 'arf!" said C, who is a good deal of a Cockney.

"There!" said H with a sigh, "I told you so."

"There's no doubt that our friend the aspirate has done it this year," said T; "but some of us are not downhearted. Look at all my Tyldesleys."

"We're quite willing to look at them," said C, "but don't ask us to count them. Meanwhile what about my Cook in the same county? And good old hard-working Coe and Cox?"

"Yes," said L, "and what about Lancashire itself—almost at the top of the tree? And Lee of Middlesex? H may have the greatest number of heroes, but we're not to be sneezed at. And even his wonderful Hobbs couldn't win the championship. It rested between M and me. I'm proud to be M's next-door neighbour."

"It's been a great season for me," said M. "I admit to being nervous on the second day of the last great match, but all's well now. What a game that was! And it's not only of Middlesex that I'm proud; if you glance at the batting averages you will notice Mead not a great way removed from the top; and Makepeace not far below him, and I hold Murrell in special esteem."

"Yes," said R, "and if you continue to look you will find Rhodes at the head of the bowling, and Rushby and Richmond in honourable places, and the steady Russell with over two thousand runs to his name. There are also two brothers named Relf. Good heavens, the H's aren't everything!"

"He doesn't claim, I hope," B struck in, "that Brown begins with H, or Bowley, or Bat or Ball or Bails?"

"Nor," said S, "that Sandham and Sutcliffe and Stevens and Seymour and the gallant little Strudwick (who, like all wicket-keepers, is so liable to be overlooked) never existed? Not to mention my latest recruit, Mr. Skeet? Some letters can be too haughty and—"

"Grasping," said G. "But all of you must be careful of me. I carry big Gunns."

"Although I'm not too prominent," said F, "I've got a very dangerous bowler and hitter and captain in Fender, to say nothing of two Freemen and a 'Fairy.' And during the season C.B. Fry bobbed up once to some purpose."

I asked one or two of the letters to explain their silence.

"Well," said Z, "cricket has never interested me. But then my range is very narrow."

"And mine's even narrower," sighed X.

"If it weren't for Quaife," said Q, "I should be in despair and play nothing but a quiet game of quoits now and again."

"H may have that long string," said W, "but he breaks down badly here and there. Where's his six-foot-six left-handed bowler and bat? He hasn't got one. I have, though, in Woolley. And where's his master of the game, practical and theoretical, in a harlequin cap? The wisest captain any county ever had and the most enthusiastic and stimulating? In short, where is H's P.F. Warner, whom we're all so sorry to lose, but who had such a glorious farewell performance? Where? Ha!"

"I claim a share in the Middlesex captain," said P proudly. "For is he not a Plum? I hate to see him go, but I shall not be fruitless; look how Peach is coming along."

"And who owns the All-English Captain, I should like to know?" said the deep voice of D. "Not to mention a Denton and a Durston and a Dolphin and a Dipper. It is something to own a Dean; it is more to possess a Ducat."

"Isn't life going to be very dull for all of you till next May?" I asked.

"Oh, no," said A, who hitherto had not spoken. "We're going to follow the English team's doings in Australia. And won't it be A1 when they bring back the Ashes?"

"Absolutely," I agreed.

"Tuesday next, I may explain, is Belfastese for Tuesday next, and means to-day."—Daily Paper.

Generosity at the Grocer's: "Provided you get one bad egg from us, we will on your returning it give you two for it."

From an engineer's letter:—

"We are exhibiting ——'s Patent Nibbling Machine at the Laundry Trades Exhibition."

We have often wondered how our collars get those crinkled edges.

"The club before declaring at 5 wickets had put up a formidable score of 341, Major Ireland making 434 and Capt. Green 127.

Capt. M.A. Green, stpd. Mistri b. Evan 27 Maj. K.A. Ireland, c. & b. Bignall 134 Newnham, b. Evans 4 Lieut. Foley, b. Evans 4 Maj. Englefield, b. Powers 22 Lieut. Cambon not out 15 Extras 35 Total for 5 wickets misdeclared 341 Egyptian Gazette.

We thought from the start that something was wrong.

The Rector. "Very nice, Mrs. Brown. Very creditable indeed. But personally I consider the marrow a much overrated vegetable, apart, of course, from its decorative value at harvest festivals."

Nimrod he was a hunter in the days of long ago,

Caring little for things of state, little for things of show;

When the unenlightened around him squabbled for wealth or fame

Nimrod fled to the forests and gave himself up to Game.

I've never been told what jungles old Nimrod called his own,

Or studied the "Sportsman's Record" he scratched on a shoulder-bone;

I haven't heard what he shot with nor even what game he slew,

But I know he was fore-forefather to fellows like me and you.

He stood to the roaring tiger, he stood to the charging gaur;

His was the love of the hunting which is more than the lust of war;

He knew the troubles of tracking, the business of camps and kits,

And the pleasure that pays for the pain of all—the ultimate shot that hits.

Now I've nowhere seen it stated, but I'm certain the thing occurred,

That when Nimrod came to his death-bed he sent his relatives word,

And said to his sons and his people ere his spirit obtained release,

"You follow the trails I taught you and your ways will bring you peace."

Wherefore—as now and to-morrow—when the souls of men were sick,

When wives were fickle or fretful or the bills were falling thick,

When the youth was minded to marry and the maiden withheld consent,

Heeding the words of Nimrod, they packed their spears and went—

Went to the scented mornings, to the nights of the satin moon

That can lap the heart in solace, that can settle the soul in tune;

So they continued the remedy Nimrod of old began—

The healing hand of the jungle on the fevered brow of man.

Then—as now and to-morrow—mended and sound and sane,

Flushed by the noonday sunshine, freshed by the twilight rain,

Trailing their trophies behind them, armed with the strength of ten,

Back they came from the jungle ready to start again.

* * * * *

Ye who have travelled the wilderness, ye who have followed the chase,

Whom the voice of the forest comforts and the touch of the lonely place;

Ye who are sib to the jungle and know it and hold it good—

Praise ye the name of Nimrod, a Fellow Who Understood.

H.B.

"Two-and-a-half Miles from Station with Non-stop Trains."—Weekly Paper.

"TEN PROFESSORSHIPS VACANT

In Sydney University.

The giant British aeroplane G.E.A.T.L., from Cricklewood aerodrome, London, landed at Blecherette, Lausanne, at 6-5 this evening."—Irish Paper.

Did all the ten Sydney Professors fall out of it together?

"The Prude's Fall."

Though the hero is French and takes up his residence in an English cathedral town in order to rectify our British prudery and show us how to make love, there is practically nothing here that is calculated to bring a blush to the cheek of modesty. It is true that from time to time Captain le Briquet kisses various outlying portions of his "ange ador?," but it is all very decorous and his ultimate intentions are strictly respectable.

You see, he was really just playing a game. Big game was his speciality (Africa) and this one was to be as big as an elephant. It consisted in the correction of a flaw which he had found in the object of his worship, the lovely young Widow Audley, who had refused in his very presence to receive a woman, an old friend of hers, who had preferred love to reputation. He, the gallant Captain, proposed to amend this error. By his French methods he would reduce the Widow to such a state of helplessness that she would consent to become his mistress. The fact that he happened to be a bachelor, and perfectly free to marry her, should not be allowed to stand in the way of his scheme. He would explain that the exigencies of his vocation as a hunter of big game demanded a greater measure of liberty than was practicable within the bonds of matrimony. He would be "faithful but free."

In the course of a brief month (the interval between the First and Second Acts, for we are not permitted to see how he does it) she has become as putty in his hands. She consents to be his mistress, and is indeed so determined to adopt this informal style of union that when he produces a special marriage licence she is indignant at such a concession to the proprieties. But once again the Captain proves irresistible with his French methods and all ends well.

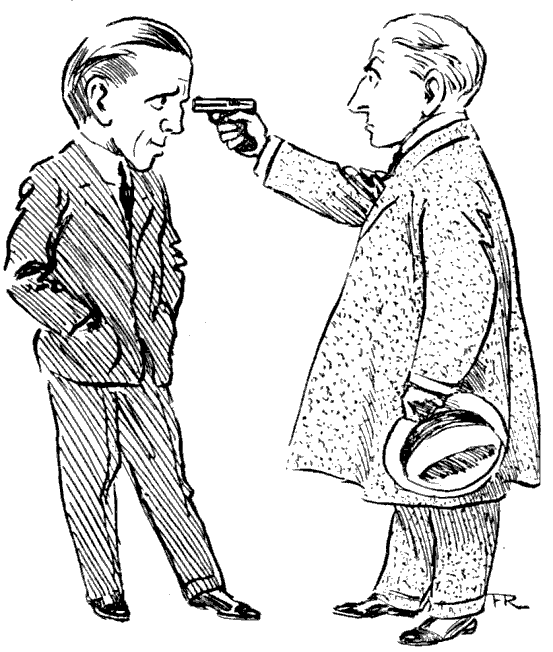

THE CAPTAIN "EXAMINES ARMS."

Captain le Briquet ... Mr. Gerald du Maurier.

Sir Nevil Moreton, Bart. ... Mr. Franklin Dyall.

Mr. Gerald du Maurier was the life and soul of the play, which would have been a dullish business without him. His reappearances were always hailed as a joyous relief to the prevailing depression. Even Dean Carey—most delightful in the person of Mr. Gilbert Hare—became at one time a gloomy Dean; and Miss Lilian Braithwaite, who played very tenderly in the part of Mrs. Westonry (the lady who had lost her reputation), could not hope to be very entertaining with her reminiscences of a lover whom we had never had the pleasure of meeting.

Mrs. Audley again (treated naturally and with a pleasant artlessness by Miss Emily Brooke) did not take very kindly to the conquest of her scruples and gave little suggestion of the rapture of surrender. Further, the authors paid a poor compliment to English gentlemen by providing the Captain with a dull boor for his rival. The contrast was a little too patent. Even so Mr. Franklin Dyall might perhaps have made the r?le of Sir Nevil Moreton appear a little less impossible. But, however good he may be in character parts or where melodrama is indicated, he never allowed us to mistake him for a British Baronet. The only person (apart from le Briquet) who contributed nothing to the general gloom was the Dean's wife, played with the most attractive grace and humour by Miss Nina Boucicault.

A note of piquancy was given to Mr. du Maurier's part by his broken English. "Broken" is perhaps not quite the word, unless we may speak of a torrent as being broken by pebbles in its bed. There were momentary hesitancies, and a few easy French words, such as pardon? pourquoi donc? c'est permis? alors, were introduced to flatter the comprehension of the audience; but for the rest his fluency—and at all junctures, even the most unlikely—was simply astounding. Few people, speaking in their native tongue, can ever have commanded so facile an eloquence. What chance had a mere Englishman against him?

The action of The Prude's Fall was supposed to take place in 1919, but its atmosphere was clearly ante-bellum. Anyhow there was no sign of the alleged damage done to our moral standards by the War. But nobody will quarrel on that ground with Mr. Besier and Miss Edginton, the clever authors of this very interesting play. And if we have to be taught how to behave by a Frenchman, to the detriment of our British amour propre, there is nobody who can do it so nicely and painlessly as Mr. du Maurier.

"Wedding Bells."

I begin to suspect that the possible situations of marital farce are becoming exhausted. Certainly we have lost the power of being staggered by the emergence of an old wife out of the past. But Mr. Salisbury Field, who wrote Wedding Bells for America, is not content with a single repetition of this ancient device; he must needs give us these intrusions in triplicate, showing how they affect the career of (1) the hero, (2) his man-servant, (3) a poet-friend. True he only produces two old wives; but one of them, being a bigamist, was able to intrude "in two places" (as the auctioneers say).

The wife of Reginald Carter (Mr. Owen Nares), having first run right away from him and then apparently divorced him for desertion (I told you the play was American), turns up on the eve of his marriage to another. He has barely recovered from his failure to keep his future wife in ignorance of his past when he has to start taxing his brains all over again in order to keep his past wife in ignorance of his future.

The First Act went well enough and was full of good words—not very subtle perhaps, but the kind that invites intelligent laughter. Later the play degenerated into something too improbable for comedy and not boisterous enough for pure farce. The two most disintegrating elements were furnished by a love-sick poet (a figure that should have been vieux jeu in the last century) and an English maid who could never have existed outside the imagination of an American. I make no complaint of the fact that in a chequered past she had married both Carter's man-servant and the antiquated poet; but I do complain that her Cockney accent was imperfectly consistent both with her rustic origin an apple-cheeked lass, we were told, from somewhere in Kent) and her situation as maid to a very smart American.

You will naturally ask what Mr. Owen Nares was doing in this galley; and I cannot tell you. I can only say that he was very brave about it all. In [pg 197] a sense it was a serious performance, the only one of its kind in the play; yet not serious enough to serve as a foil for the general frivolity, for he was constantly bringing his own high sentiments into ridicule, and so burlesquing the Owen Nares that we love to take seriously.

On the other hand, Miss Gladys Cooper, as Rosalie, his late wife, was untroubled by high sentiment; she was content to be wayward and unseizable, confident in the obvious power of her charm to retrieve him from the very altar-rails. Her own heart never seemed to come into the question, and her motive in setting herself to recover him was not much clearer than her reason for deserting him.

Some of the minor characters gave good entertainment. There was a dude (is that what they call them now in America?) who dressed very perfectly and said a great many funny things all well within the range of his own, and our, intelligence. Mr. Deverell played the part with admirable restraint. And we could ill have spared the humours of Carter's man Jackson (Mr. Will West), whose wide experience in matrimony, resulting in an attitude alternately timorous and prehensile towards female society in the servants' hall, was the source of many poignant generalisations. Miss Edith Evans, as a mother-in-law manqu?e, showed a touch of real artistry; and Mr. George Carr had no difficulty in getting fun out of the part of a Japanese house-boy, almost the only novelty which we owed to the American origin of the play.

When Carter was turned down by a clergyman who refused to perform the marriage rites for a divorced man, there was something very attractive (to a golfer) in his protest against these "local rules." This was one of many good things said; but the play had its dull times too, and there were one or two lapses made in the pursuit of the easy laugh. For instance:—

Carter. "Do you believe in God?"

Wills. "Good God!" (laughter).

[Carter here kneels down to get something from under the sofa.

Wills. "Are you going to pray?" (laughter).

Personality, of course, counts for much, and both Miss Gladys Cooper and Mr. Owen Nares have enough admirers to ensure a success for this rather moderate farce. But not a triumph, I fear; for, after all, the play counts for something too and, though all the Faithful may be trusted to put in one appearance, I doubt if many outside the ranks of the Very Faithful will turn again at the sound of these Wedding Bells.

More Direct Action.

"Northumberland Miners' Executive have decided to have Mr. Robert Smillie's portrait painted in oils for Burt Hall, Newcastle.

Other matter relating to the coal crisis appears on Page Eleven."—Daily Telegraph.

"DAY BY DAY.

Well, did you get your gun and have a shot at the pheasants and the partridges yesterday?"—Scotch Paper, Sept. 2nd.

Naturally; the same gun with which we knocked the grouse over in July.

"Temp. in Shade.—Max. of past 24 hours. Hyderabad (Sind) ... 941?2."—Indian Paper.

Good for the Sinders.

"One Dog with fairy tail came to my house, ——, Srimanta Dey's Lane, may be restored to the owner on satisfactory proof."—Statesman (Calcutta).

The evidence of a dog like that would of course be useless.

"The Cathedral Choristers received a flattening reception."—Provincial Paper.

That should "learn" them to sing sharp.

There was a young man of Combe Florey

Who wrote such a gruesome short story,

The English Review

Found it rather too blue

And Masefield pronounced it too gory.

(The Japanese Commander-in-Chief.)

The famous commanders of old

Were highly and duly extolled,

But their names, as recorded in song,

As a rule were excessively long—

Unlike that new broth of a boy,

The Japanese General Oi.

For we've bettered in numerous ways

Those polysyllabic old days,

And the names that confounded the Bosch

Were monosyllabic—like Foch;

But for brevity minus alloy

Give me Generalissimo Oi.

Napoleon now is napoo;

Alexander, Themistocles, too;

And you could not find space on the screen

For Miltiades, plucky old bean,

Or the names of the heroes of Troy;

But there's plenty of room for an Oi.

I picture him frugal of speech,

But in action a regular peach—

A figure that might be compared

With a Highlander, chieftain or laird,

Like The Mackintosh, monarch of Moy,

Redoubtable General Oi.

Anyhow, with so striking a name

You'd be sure of success if you came

To our shores, and might get an invite

To Elmwood to stay for the night,

And sit for your portrait to "Poy,"

Irresistible General Oi.

So here's to you, excellent chief,

Whose name is so tunefully brief.

May your rule be productive of peace,

Like that of our good Captain Reece,

And no murmur, no οτοτοτοι

Be raised over General Oi!

By our Piscatorial Expert.

I have read with great interest, tempered by a little disappointment, the article of Mr. F.A. Mitchell-Hedges on "Big Game Fishing in British Waters," in The Daily Mail of September 1st. He tells us of his experiences in catching the "tope," a little-known fish of the shark genus which may be caught this month at such places as Herne Bay, Deal, Margate, Ramsgate, Brighton and Bournemouth, where he has captured specimens measuring 7? feet long within two hundred-and-fifty yards of the shore.

Personally I have a great respect for the tope and for the topiary art, but I cannot help regretting that Mr. Mitchell-Hedges has omitted all mention of another splendid fish, the stoot, which visits our shores every year in the late summer and may be caught at places as widely distant as Barmouth and Great Yarmouth, Porthcawl and Kylescue.

The stoot, be it noted, is a cross between the porpoise and the cuttle-fish; hence its local name of the porputtle. It is a clean feeder, a great fighter and a great delicacy, tasting rather like a mixture of the pilchard, the anchovy and the Bombay duck.

For tackle I recommend a strong greenheart bamboo pole, like those used in pole-jumping, about eighteen feet in length, and about three hundred yards of wire hawser, with a Strathspey foursome reel sufficiently large to hold it. Do not be afraid of the size of the hook. The stoot-fisher cannot afford to take any risks. I do not wish to dogmatise, but it must be big enough to cover the bait. And the stoot is extremely voracious. Almost anything will do for bait, if one remembers, as I have said above, that the stoot is a clean feeder. At different times I have tried a large square of corridor soap, a simulation pancake, three pounds of tough beefsteak or American bacon, or a volume of Sir Henry Howorth's History of the Mongols, and never without satisfactory results.

On arriving at the feeding ground of the stoot, cast your line well out from the boat with a small howitzer. You wait anxiously for the first bite; suddenly the hawser runs taut and there is a scream from the reel. But do not be afraid of the reel screaming. In the circumstances it is a very good sign. Plant the butt of your rod or pole firmly in the socket fitted for the purpose in all motor-stooter boats and let the fish run for about a parasang, and then strike and strike hard. The battle is now begun. Be prepared for a series of tremendous rushes. You will see the stoot's huge bulk dash out of the water; you will hear his voice, which resembles that of the gorilla. This may go on for a long time: if the stoot be full-grown it will take you quite an hour to bring him alongside the boat. Then comes the problem of how to get him in—the hardest of all. The gaff, if possible a good French gaffe, is indispensable, but the kilbin, a marine life-preserver resembling a heavy niblick, is a handy weapon at this stage of the conflict. Strike the fish on the head repeatedly—but never on the tail—until he is paralysed and then grasp him firmly by the metatarsal fin or, failing that, by the medulla oblongata, but keep your hands away from his mouth. The teeth of the stoot are terribly sharp and pyorrhœa is not unknown in this species.

Having got the fish on board you will need a spell of rest. An hour's battle with a stoot is the most sudorific experience that I know, even more so than my contests with red snappers at Mazatlan, in Mexico, or bat-fish off the coasts of Florida. A complete change is necessary.

I have already spoken of the eating qualities of the stoot, which exceed those of the tope. One is enough to provide sustenance for a small country congregation. Cooked en casserole, or filleted, or grilled and stuffed with Carlsbad plums, it is delicious.

And lastly it lends itself admirably to curing or preserving. Bottled stoot is in its way as nutritious as Guinness's.

London Pride.

There was a haughty maiden

Who lived in London Town,

With gems her shoes were laden,

With gold her silken gown.

"In all the jewelled Indies,

In all the scented East,

Where the hot and spicy wind is,

No lady of the best

Can vie with me," said None-so-pretty

As down she walked through London City.

"Our walls stand grey and stately;

Our city gates stand high;

Our lords spend wide and greatly;

Our dames go sweeping by;

Our heavy-laden barges

Float down the quiet flood

Where on the pleasant marges

Gay flowers bloom and bud.

Oh, there's no place like London City,

And I'm its crown," said None-so-pretty.

The fairies heard her boasting,

And that they cannot bear;

So off they went a-posting

For charms to bind her there.

They wove their spells around her,

The maiden pink and white;

With magic fast they bound her,

And flowers sprang to sight

All white and pink, called None-so-pretty,

The Pride of dusty London City.

"A City pigeon swooped down suddenly out of nowhere and all but took the cap off a bricklayer at the rate of forty miles an hour."—Daily Paper.

It will be observed that the speed was that of the bird and not the bricklayer.

"At —— Church, on Monday last, a very interesting wedding was solemnised, the contracting parties being Mr. Richard ——, eldest son of Mr. and Mrs. ——, and a bouquet of pink carnations."—Welsh Paper.

There has been nothing like this since Gilbert wrote of—

"An attachment ? la Plato

For a bashful young potato."

"Wot yer mean photographin' my wife? I saw yer."

"You're quite mistaken; I—I wouldn't do such a thing."

"Wot yer mean—wouldn't? she's the best-lookin' woman on the beach."

(By Mr. Punch's Staff of Learned Clerks.)

Miss Sheila Kaye-Smith continues to be the chronicler and brief abstractor of Sussex country life. Her latest story, Green Apple Harvest (Cassell), may lack the brilliant focus of Tamarisk Town, but it is more genuine and of the soil. There indeed you have the dominant quality of this tale of three farming brothers. Never was a book more redolent of earth; hardly (and I mean this as a compliment) will you close it without an instinctive impulse to wipe your boots. The brothers are Jim, the eldest, hereditary master of the great farm of Bodingmares; Clem, the youngest, living contentedly in the position of his brother's labourer; and Bob, the central character, whose dark and changing fortunes make the matter of the book, as his final crop of tragedy gives to it the at first puzzling title. There is too much variety of incident in Bob's uneasy life for me to follow it in detail. The tale is sad—such a harvesting of green apples gives little excuse for festival—but at each turn, in his devouring and fatal love for the gipsy, Hannah, in his abandonment by her, and most of all in his breaking adventures of the soul, now saved, now damned, he remains a tragically moving figure. Miss Kaye-Smith, in short, has written a novel that lacks the sunshine of its predecessors, but shows a notable gathering of strength.

Would you not have thought that at this date motor-cars had definitely joined umbrellas and mothers-in-law as themes in which no further humour was to be found? Yet here is Miss Jessie Champion writing a whole book, The Ramshackle Adventure (Hodder and Stoughton), all about the comical vagaries of a cheap car—a history that, while it has inevitably its dull moments, has many more that are both amusing and full of a kind of charm that the funny-book too often conspicuously lacks. I think this must be because almost all the characters are such human and kindly folk, not the lay figures of galvanic farce that one had only too much reason to expect. For example, the owner of the car is a curate, whose wife is supposed to relate the story, and George has to drive the Bishop in his unreliable machine. Naturally one anticipates (a little drearily) upsets and ditches and episcopal fury, instead of which—well, I think I won't tell you what happens instead, but it is something at once far more probable and pleasant. I must not forget to mention that the cast also includes a pair of engaging lovers whom eventually the agency of the car unites. Indeed, to pass over the lady would display on my part the blackest ingratitude, since among her many attractive peculiarities it is expressly mentioned that she (be still, O leaping heart!) reads the letter-press in Punch.

Mrs. Edith Mary Moore has devoted her great abilities to proving in The Blind Marksman (Hodder and Stoughton) how shockingly bad the little god's shooting became towards the end of last century. She proves it by the frustrated hopes of Jane, her heroine, who in utter ignorance of life marries a man whose pedestrian attitude of mind is quite unfitted to keep pace with her own passionate and eager hurry of idealism. She becomes household drudge to a master who cannot even talk the language which she speaks naturally, and discovers in a man she has known all her life the lover she should have married, only to lose [pg 200] him in the European War. Here you have both Jane and the ineffective husband—for whom I was sincerely sorry, because he asked so very little of life and didn't even get that—badly left, and the case against Cupid looks black. Mrs. Moore does what she can for him by blaming our Victorian ancestors and their habits of mind; but I think it is only fair to add that, delightful as Jane is, she was not made for happiness any more than the people who enjoy poor health have it in them to be robust, and that, true as much of the author's criticism is, she has not been able to give The Blind Marksman, for his future improvement, any very helpful ideas as to how he is to shoot.

The Devil, in so far as I have met him in fiction, has usually been a highly successful intriguer on behalf of anyone prepared to make the necessary bargain. Sir Ronald Ross, however, to judge from the rather confused medi?val happenings in the Alps which are faithfully described in The Revels of Orsera (Murray), has rather a low opinion of the intelligence of Mephistopheles. Anyhow, a certain Zozimo, deformed in body but of great romantic sensibility, appears to have exchanged his outward presence for that of a rich and handsome young Count, and in this guise wooed the Lady Lelita, for whose sake her father had devised a magnificent contest of suitors at Andermatt in the year 1495. After a great deal of preliminary bungling the supposititious Count, with the Devil in Zozimo's shape as his body-servant, was just about to secure the object of his affections when Zozimo was stabbed by his mother, with the result that the double identity was fused and the Lady Lelita was left with a dying dwarf as her knight. If the plot of The Revels of Orsera is a little unsatisfying the elaboration of scenic description and medi?val pageantry is conscientious in the extreme, and the laughter which followed the malicious pranks of Gangogo, the professional jester of the tourney, must, if I am to take the author's word for it, have made the glaciers ring. There is a great deal in the way of philosophy and psychology that is very baffling in this book, but of one thing I feel certain, and that is that the Elemental Spirits of the Heights, to whom frequent allusion is made, must find the winter sports of a later age a sorry substitute for the rare old frolics of the fifteenth century.

It can at least be claimed for Mrs. Margaret Baillie Saunders that she has provided an original setting and "chorus" for her new novel, Becky & Co. (Hutchinson). Tales of City courtship have been written often enough, but the combination here of a millinery establishment and a community of Little Sisters of St. Francis under one roof in the Minories, gives a stimulating atmosphere to a story otherwise not specially distinguished. Becky was, as perhaps you may have guessed, head of the millinery business, next door to which was housed the firm of Ray, St. Cloud & Stiggany, leather-dressers, the three partners in which all presently become suitors for the hand of Becky. This in effect is the story—under which thimble will the heart of the heroine be eventually found?—a problem that, in view of the obviously superior claims of young St. Cloud over his two elderly rivals, will not leave you long guessing. An element of novel complication is however furnished by the device of making St. Cloud at first engaged to Ray's daughter, who, subsequently retiring into the Franciscan sisterhood, left her fianc? free to become the rival of her widowed father. (As the late Dan Leno used to observe, this is a little intricate!) For the rest, as I have said, an agreeable, very feminine story of mingled sentiment, commerce and ecclesiastical interest, the last predominating.

It is possible that The Sea Bride (Mills and Boon) may be too violent to suit all tastes, for Mr. Ben Ames Williams writes of men primitive in their loves and hates, and he describes them graphically. The scenes of this story are set on the whaler Sally, commanded by a man of mighty renown in the whaling world. When we meet him he has passed his prime and has just taken unto himself a young wife. She goes with him in the Sally, and the way in which Mr. Williams shows how her courage increases as her husband's character weakens wins my most sincere admiration. His tale would be nothing out of the common but for his skill in giving individuality to his characters. Things happen on the Sally, bloodthirsty, sinister, terrible things, which the author neither glosses nor gloats over, being content to make them appear essential to the development of the story. I am going to keep my eye on Mr. Williams, chiefly because he can write enthrallingly, but partly to see if he will accept a word of advice and be a little more sparing in his use of those little dots ... which are the first and last infirmity of writers who have no sense of punctuation.

When a young man sets out to London to make money for his relations he usually (in a novel) writes a book which sells prodigiously—quite an easy thing to do in a novel. Mr. John Wilberforce, however, avoids the beaten track in The Champion of the Family (Fisher Unwin). Jack Brockhurst, the champion in question, became a member of the Stock Exchange, and, if you will accept my invitation and follow his fortunes, I can promise you a fluttering time. Mr. Wilberforce's name is unknown to me, and I judge him more experienced in the mysteries of the Stock Exchange than in the art of fiction; but I like his constructive ability and I like his courage. He does not hesitate to make his champion a prig, which is exactly what a youth so idolised by his family would be likely to become. But, though a prig by training, Jack was not by nature a bore, and his relations (especially his father and sister) are delightful people. Altogether I find this a most promising performance.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol.

159, September 8th, 1920, by Various

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH ***

***** This file should be named 16877-h.htm or 16877-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/1/6/8/7/16877/

Produced by Jonathan Ingram, Keith Edkins and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net