Economy of the Republic of Ireland

Background Information

This wikipedia selection has been chosen by volunteers helping SOS Children from Wikipedia for this Wikipedia Selection for schools. SOS mothers each look after a a family of sponsored children.

| Economy of Ireland | |

|---|---|

Dublin City Centre |

|

| Rank | 44th (2011 est.) |

| Currency | 1 Euro = 100 cent(s) |

| Fiscal year | Calendar year |

| Trade organisations | EU, WTO and OECD |

| Statistics | |

| GDP | €159 bn (2011, current prices) |

| GDP growth | 1.4% (2011) |

| GDP per capita | $42,920 (2011 est.) |

| GDP by sector | services (69%), industry (29%), agriculture (2%) (2010 est.) |

| Inflation ( CPI) | 2.5% (2011 est.) |

| Population below poverty line |

6.2% (consistent poverty in 2010) |

| Gini coefficient | 33.9 (2010) |

| Labour force | 2.126 million (2011 est.) |

| Labour force by occupation |

services (76%), industry (19%), agriculture (5%) (2011 est.) |

| Unemployment | 15.1 % (September 2012) |

| Average gross salary | 2,764 € / 3,731 $, monthly (2006) |

| Average net salary | 2,025 € / 2,733 $, monthly (2006) |

| Main industries | pharmaceuticals, chemicals, computer hardware and software, food products, beverages and brewing, medical devices. |

| Ease of Doing Business Rank | 15th |

| External | |

| Exports | $124.3 billion (2011 est.) |

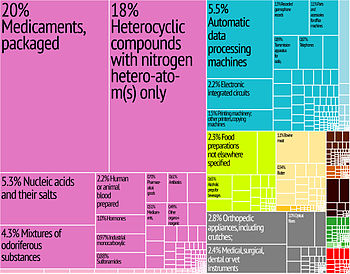

| Export goods | machinery and equipment, computers, chemicals, medical devices, pharmaceuticals, food products, animal products. |

| Main export partners | US 23.2%, UK 15.4%, Belgium 14.3%, Germany 8.1%, France 5%, Switzerland 4% (2010) |

| Imports | $71.35 billion (2011 est.) |

| Import goods | data processing equipment, other machinery and equipment, chemicals, petroleum and petroleum products, textiles, clothing. |

| Main import partners | UK 32.1%, US 14.1%, Germany 7.7%, China 6.4%, Netherlands 4.9% (2010) |

| Gross external debt | $2.352 trillion (30 September 2011) |

| Public finances | |

| Public debt | €169.2 billion (108.2% of GDP in 2011) |

| Budget deficit | €20.5 billion (-13.1% of GDP in 2011) |

| Revenues | €55.8 billion (35.7% of GDP in 2011) |

| Expenses | €76.2 billion (48.7% of GDP in 2011) |

| Economic aid | Donor of ODA: $585 mn (2010) Recipient of agricultural aid: $895 mn (2010) |

| Credit rating | Standard & Poor's: BBB+ (Domestic) BBB+ (Foreign) AAA (T&C Assessment) Outlook: Negative Moody's: Baa3 Outlook: Negative Fitch: BBB+ Outlook: Stable |

| Foreign reserves | $2.188 billion (February 2012) |

|

Main data source: CIA World Fact Book |

|

The economy of the Republic of Ireland is a modern knowledge economy, focusing on services and high-tech industries and dependent on trade, industry and investment. In terms of GDP per capita, Ireland is ranked as one of the wealthiest countries in the OECD and the EU-27 at 5th in the OECD-28 rankings as of 2008. In terms of GNP per capita, a better measure of national income, Ireland ranks below the OECD average, despite significant growth in recent years, at 10th in the OECD-28 rankings. GDP (national output) is significantly greater than GNP (national income) due to the repatriation of profits and royalty payments by multinational firms based in Ireland.

A 2005 study by The Economist found Ireland to have the best quality of life in the world. The 1995 to 2007 period of very high economic growth, with a record of posting the highest growth rates in Europe, led many to call the country the Celtic Tiger. Arguably one of the keys to this economic growth was a low corporation tax, currently at 12.5% standard rate.

The Financial Crisis of 2008 affected the Irish economy severely, compounding domestic economic problems related to the collapse of the Irish property bubble. After 24 years of continuous growth at an annual level during 1984-2007, Ireland first experienced a short technical recession from Q2-Q3 2007, followed by a long 2-year recession from Q1 2008 - Q4 2009. In March 2008, Ireland had the highest level of household debt relative to disposable income in the developed world at 190%, causing a further slow down in private consumption, and thus also being one of the reasons for the long lasting recession. The hard economic climate was reported in April 2010, even to have led to a resumed emigration.

After a year with side stepping economic activity in 2010, Irish real GDP rose by 1.4% in 2011. The economic challenges continued, however, with some economists fearing the European sovereign-debt crisis had suddenly caused a new Irish recession starting in Q1 2012, when the Central Statistics Office announced that seasonally adjusted quarterly real GDP had contracted by -1.1%. The figure was however later revised to -0.5%, and the recession threat was avoided by a small positive growth in the subsequent two quarters, mainly due to strongly driven improvements from the export sector. In November 2012 the European Commission's economic forecast for Ireland showed positive growth overall in 2012 at 0.4%, followed by increasing growth rates to 1.1% in 2013 and 2.2% in 2014.

History

Since the Irish Free State

From the 1920s Ireland had high trade barriers such as high tariffs, particularly during the Economic War with Britain in the 1930s, and a policy of import substitution. During the 1950s, 400,000 people emigrated from Ireland. It became increasingly clear that economic nationalism was unsustainable. While other European countries enjoyed fast growth, Ireland suffered economic stagnation. The policy changes were drawn together in Economic Development, an official paper published in 1958 that advocated free trade, foreign investment, and growth rather than fiscal restraint as the prime objective of economic management.

In the 1970s, the population increased by 15% and national income increased at an annual rate of about 4%. Employment increased by around 1% per year, but the state sector amounted to a large part of that. Public sector employment was a third of the total workforce by 1980. Budget deficits and public debt increased, leading to the crisis in the 1980s. During the 1980s, underlying economic problems became pronounced. Middle income workers were taxed 60% of their marginal income, unemployment had risen to 20%, annual overseas emigration reached over 1% of population, and public deficits reached 15% of GDP.

In 1987 Fianna Fáil reduced public spending, cut taxes, and promoted competition. Ryanair used Ireland's deregulated aviation market and helped European regulators to see benefits of competition in transport markets. Intel invested in 1989 and was followed by a number of technology companies such as Microsoft and Google. A consensus exists among all government parties about the sustained economic growth. The GDP per capita in the OECD prosperity ranking rose from 21st in 1993 to 4th in 2002.

Between 1985 and 2002, private sector jobs increased 59%. The economy shifted from an agriculture to a knowledge economy, focusing on services and high-tech industries. Economic growth averaged 10% from 1995 to 2000, and 7% from 2001 to 2004. Industry, which accounts for 46% of GDP and about 80% of exports, has replaced agriculture as the country's leading sector.

Celtic Tiger (1995-2007)

The economy benefited from a rise in consumer spending, construction, and business investment. Since 1987, a key part of economic policy has been Social Partnership, which is a neo-corporatist set of voluntary 'pay pacts' between the Government, employers and trade unions. The 1995 to 2000 period of high economic growth was called the "Celtic Tiger", a reference to the " tiger economies" of East Asia.

GDP growth continued to be relatively robust, with a rate of about 6% in 2001, over 4% in 2004, and 4.7% in 2005. With high growth came high inflation. Prices in Dublin were considerably higher than elsewhere in the country, especially in the property market. However, property prices are falling following the recent economic recession. At the end of July 2008, the annual rate of inflation was at 4.4% (as measured by the CPI) or 3.6% (as measured by the HICP) and inflation actually dropped slightly from the previous month.

In terms of GDP per capita, Ireland is ranked as one of the wealthiest countries in the OECD and the EU-27, at 4th in the OECD-28 rankings. In terms of GNP per capita, a better measure of national income, Ireland ranks below the OECD average, despite significant growth in recent years, at 10th in the OECD-28 rankings. GDP is significantly greater than GNP (national income) due to the large amount of multinational firms based in Ireland. A 2005 study by The Economist found Ireland to have the best quality of life in the world.

The positive reports and economic statistics masked several underlying imbalances. The construction sector, which was inherently cyclical in nature, accounted for a significant component of Ireland's GDP. A recent downturn in residential property market sentiment has highlighted the over-exposure of the Irish economy to construction, which now presents a threat to economic growth. Despite several successive years of economic growth and significant improvements since 2000, Ireland's population is marginally more at risk of poverty than the EU-15 average and 6.8% of the population suffer "consistent poverty".

Ireland is currently ranked as the world's third most "economically free" economy in an index created by free-market economists from the Wall Street Journal and Heritage Foundation, the Index of Economic Freedom.

Financial Crisis (2008-)

It was the first country in the EU, to officially enter a recession related to the Financial crisis 2008, as declared by the Central Statistics Office. Ireland now has the second-highest level of household debt in the world (190% of household income). The country's credit rating was downgraded to "AA-" by Standard & Poor's ratings agency in August 2010 due to the cost of supporting the banks, which would weaken the Government's financial flexibility over the medium term. It transpired that the cost of recapitalising the banks was greater than expected at that time, and, in response to the mounting costs, the country's credit rating was again downgraded by Standard & Poor's to "A".

The global recession has significantly impacted the Irish economy. Economic growth was 4.7% in 2007, but -1.7% in 2008 and -7.1% in 2009. In mid 2010, Ireland looked like it was about to exit recession in 2010 following growth of 0.3% in Q4 of 2009 and 2.7% in Q1 of 2010. The government forecast a 0.3% expansion. However the economy experienced Q2 negative growth of -1.2%, and in the fourth quarter, the GDP shrunk by 1.6%. Overall, the GDP was reduced by 1% in 2010, making it the third consecutive year of negative growth. On the other hand Ireland recorded the biggest month-on-month rise for industrial production across the eurozone in 2010, with 7.9% growth in September compared to August, followed by Estonia (3.6%) and Denmark (2.7%).

Bank solvency

The second problem, unacknowledged by management of Irish banks, the financial regulator and the Irish government, is solvency. The question concerning solvency has arisen due to domestic problems in the crashing Irish property market. Irish financial institutions have substantial exposure to property developers in their loan portfolio. These property developers are currently suffering from substantial over-supply of property, much still unsold, while demand has evaporated. The employment growth of the past that attracted many immigrants from Eastern Europe and propped up demand for property has been replaced by rapidly rising unemployment.

Irish property developers speculated billions of Euros in overvalued land parcels such as urban brownfield and greenfield sites. They also speculated in agricultural land which, in 2007, had an average value of €23,600 per acre ($32,000 per acre or €60,000 per hectare) which is several multiples above the value of equivalent land in other European countries. Lending to builders and developers has grown to such an extent that it equals 28% of all bank lending, or "the approximate value of all public deposits with retail banks. Effectively, the Irish banking system has taken all its shareholders' equity, with a substantial chunk of its depositors' cash on top, and handed it over to builders and property speculators.....By comparison, just before the Japanese bubble burst in late 1989, construction and property development had grown to a little over 25 per cent of bank lending."

Irish banks correctly identify a systematic risk of triggering an even more severe financial crisis in Ireland if they were to call in the loans as they fall due. The loans are subject to terms and conditions, referred to as "covenants". These covenants are being waived in fear of provoking the (inevitable) bankruptcy of many property developers and banks are thought to be "lending some developers further cash to pay their interest bills, which means that they are not classified as 'bad debts' by the banks". Furthermore, the banks' "impairment" (bad debt) provisions are still at very low levels. This does not appear to be consistent with the real negative changes taking place in property market fundamentals.

In contrast, on the 7th of October 2008, Danske Bank wrote off a substantial sum largely due to property-related losses incurred by its Irish subsidiary - National Irish Bank. The 3.18% charge against the loan book of its Irish operations is the first significant write off to take place and is a modest indication of the extent of the more substantial future charges to be incurred by the over-exposed domestic banks. Asset write downs by the domestically-owned Irish banks are only now slowly beginning to take place

Guarantee of banking system

On 30 September 2008, the Irish Government declared a guarantee that intends to safeguard the Irish banking system. The Irish National guarantee, backed by taxpayer funds, covers "all deposits (retail, commercial, institutional and interbank), covered bonds, senior debt and dated subordinated debt". In exchange for the bailout, the government did not take preferred equity stakes in the banks (which dilute shareholder value) nor did they demand that top banking executives' salaries and bonuses be capped, or that board members be replaced.

Despite the Government guarantees to the banks, their shareholder value continued to decline and on 2009-01-15, the Government nationalised Anglo Irish Bank, which had a market capitalisation of less than 2% of its peak in 2007. Subsequent to this, further pressure came on the other two large Irish banks, who on 2009-01-19, had share values fall by between 47 and 50% in one day. As of 11 October 2008, leaked reports of possible actions by the government to artificially prop up the property developers have been revealed.

National Recovery Plan 2011-2014

In November 2010 the Irish Government published the National Recovery plan, which aims to restore order to the public finances and to bring its deficit in line with the EU target of 3% of economic output by 2015. It involves a budget adjustment of €15 billion (€10 billion in public expenditure cuts and €5billion in taxes) over a four-year period. This will be front loaded in 2011 where measures totaling €6 billion are planned. VAT is to increase to 23% by 2014 and a property tax and domestic water charges are to be introduced.

Sectors

Exports

Exports play an important role in Ireland's economic growth. A series of significant discoveries of base metal deposits have been made, including the giant ore deposit at Tara Mine. Zinc-lead ores are also currently mined from two other underground operations in Lisheen and Galmoy. Ireland now ranks as the seventh largest producer of zinc concentrates in the world, and the twelfth largest producer of lead concentrates. The combined output from these mines make Ireland the largest zinc producer in Europe and the second largest producer of lead.

Ireland is the world's most profitable country for US corporations, according to the US tax journal Tax Notes. The country is one of the largest exporters of pharmaceuticals and software-related goods and services in the world. Bord Gáis is responsible for the supply and distribution of natural gas, which was first brought ashore in 1976 from the Kinsale Head gas field. Electrical generation from peat consumption, as a percent of total electrical generation, was reduced from 18.8% to 6.1%, between 1990 and 2004. A forecast by Sustainable Energy Ireland predicts that oil will no longer be used for electrical generation but natural gas will be dominant at 71.3% of the total share, coal at 9.2%, and renewable energy at 8.2% of the market.

New sources are expected to come on stream after 2010, including the Corrib gas field and potentially the Shannon Liquefied Natural Gas terminal. In its Globalization Index 2010 published in January 2011 Ernst and Young with the Economist Intelligence Unit ranked Ireland second after Hong Kong. The index ranks 60 countries according to their degree of globalization relative to their GDP. While the Irish economy has significant debt problems in 2011, exporting remains a success.

Primary sector

The primary sector constitutes about 5% of Irish GDP, and 8% of Irish employment. Ireland's main economic resource is its large fertile pastures, particularly the midland and southern regions. In 2004, Ireland exported approximately €7.15 billion worth of agri-food and drink (about 8.4% of Ireland's exports), mainly as cattle, beef, and dairy products, and mainly to the United Kingdom. As the European Union's Common Agricultural Policy is conformed with, Ireland's agriculture industry is expected to decline in importance.

In the late nineteenth century, the island was mostly deforested. In 2005, after years of national afforestation programmes, about 9% of Ireland has become forested. It is still one of the least forested country in the EU and heavily relies on imported wood. Its coastline - once abundant in fish, particularly cod - has suffered overfishing and since 1995 the fisheries industry has focused more on aquaculture. Freshwater salmon and trout stocks in Ireland's waterways have also been depleted but are being better managed. Ireland is a major exporter of zinc to the EU and mining also produces significant quantities of lead and alumina.

Beyond this, the country has significant deposits of gypsum, limestone, and smaller quantities of copper, silver, gold, barite, and dolomite. Peat extraction has historically been important, especially from midland bogs, however more efficient fuels and environmental protection of bogs has reduced peat's importance to the economy. Natural gas extraction occurs in the Kinsale Gas Field and the Corrib Gas Field in the southern and western counties, where there is 19.82 bn cubic metres of proven reserves.

The construction sector, which is inherently cyclical in nature, now accounts for a significant component of Ireland's GDP. A recent downturn in residential property market sentiment has highlighted the over-exposure of the Irish economy to construction, which now presents a threat to economic growth.

While there are over 60 credit institutions incorporated in Ireland, the banking system is dominated by the Big Four - AIB Bank, Bank of Ireland, Ulster Bank and National Irish Bank. There is a large Credit Union movement within the country which offers an alternative to the banks. The Irish Stock Exchange is in Dublin, however, due to its small size, many firms also maintain listings on either the London Stock Exchange or the NASDAQ. That being said, the Irish Stock Exchange has a leading position as a listing domicile for cross-border funds. By accessing the Irish Stock Exchange, investment companies can market their shares to a wider range of investors (under MiFID although this will change somewhat with the introduction of the AIFM Directive. Service providers abound for the cross-border funds business and Ireland has been recently rated with a DAW Index score of 4 in 2012. Similarly, the insurance industry in Ireland is a leader in both retail markets and corporate customers in the EU, in large part due to the International Financial Services Centre.

Government

Welfare benefits

As of December 2007, Ireland's net unemployment benefits for long-term unemployed people across four family types (single people, lone parents, single-income couples with and without children) was the third highest of the OECD countries (jointly with Iceland) after Denmark and Switzerland. Jobseeker's Allowance or Jobseeker's Benefit for a single person in Ireland is €188 per week, as of March 2011. State provided old age pensions are also relatively generous in Ireland. The maximum weekly rate for the State Pension (Contributory) is €230.30 for a single pensioner aged between 66 and 80 (€436.60 for a pensioner couple in the same age range). The maximum weekly rate for the State Pension (Non-Contributory) is €219 for a single pensioner aged between 66 and 80 (€363.70 for a pensioner couple in the same age range).

Wealth distribution

The percentage of the population at risk of relative poverty was 21% in 2004 - one of the highest rates in the European Union. Ireland's inequality of income distribution score on the Gini coefficient scale was 30.4 in 2000, slightly below the OECD average of 31. Sustained increases in the value of residential property during the 1990s and up to late 2006 was a key factor in the increase in personal wealth in Ireland, with Ireland ranking second only to Japan in personal wealth in 2006. However, residential property values and equities have fallen substantially since the beginning of 2007 and major declines in personal wealth are expected.

Taxation

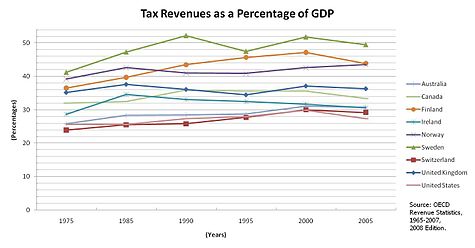

Over the past several decades, tax revenues have fluctuated at around 30% of GDP (see graph).

Currency

Before the introduction of the euro notes and coins in January 2002, Ireland used the Irish pound or punt. In January 1999 Ireland was one of eleven European Union member states which launched the European Single Currency, the euro. Euro banknotes are issued in €5, €10, €20, €50, €100, €200 and €500 denominations and share the common design used across Europe, however like other countries in the eurozone, Ireland has its own unique design on one face of euro coins. The government decided on a single national design for all Irish coin denominations, which show a Celtic harp, a traditional symbol of Ireland, decorated with the year of issue and the word Éire.