a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: The Land of Gold. Authors: Julius M(endes) Price. * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1402901h.html Language: English Date first posted: November 2014. Date most recently updated: November 2014. Produced by: Ned Overton. Project Gutenberg Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

THE LAND OF GOLD

Special Artist Correspondent of the

"Illustrated London News"

AUTHOR OF "FROM THE ARCTIC OCEAN TO THE YELLOW

SEA," ETC.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS AND SKETCHES BY THE AUTHOR

THIRD EDITION

LONDON

SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON AND COMPANY

LIMITED

St Dunstan's House

Fetter Lane, Fleet Street,

E.C.

1896

LONDON:

PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED,

STAMFORD STREET AND CHARING

CROSS.

TO

Sir WILLIAM J. INGRAM,

Bart.,

IN APPRECIATION OF

HIS GREAT INTEREST IN THE ADVANCEMENT OF

COLONIZATION AND EXPLORATION,

THIS BOOK IS RESPECTFULLY

Dedicated

BY THE AUTHOR.

I am indebted to the Proprietors of the Illustrated London News for their kind permission to reproduce, in this work, the sketches and drawings I made for them whilst on my journey, a great many of which have already appeared in that paper; and also for the use of the text accompanying them, which has formed, in a measure, the basis of my book.

Australia has recently attracted so much attention and interest amongst Englishmen, and, indeed, all over the world, that last autumn it occurred to me that a record of a visit to the western districts of the Colony might prove of some value to the public. On my mentioning the idea to Sir William Ingram of the Illustrated London News, he entered into my project with characteristic enthusiasm, and, finally, on behalf of the paper, I went out, traversed the best-known portions of the goldfields, and for the Illustrated London News I wrote a series of letters, accompanied by sketches, all of which duly appeared in the paper. Though necessarily somewhat curtailed, these articles seemed to me to attract sufficient attention, if I might judge from the letters which I received, to warrant my giving them a more permanent place, and a larger scope, in book form. The Colony, more especially in regard to its goldfields, has lately assumed so much importance in the minds of the people of Great Britain, that I feel no further apology is needed for the publication of this brief record of my journey over a continent which, until recent developments, was a comparatively little known section of the great British Empire.

| 22,

Golden Square, London, W. March, 1896. |

|

CHAPTER I. Ocean travelling of to-day—A visit to Western Australia decided upon—My outfit—The voyage on board the Oceana—Gibraltar—Suez—Aden—Colombo—The Indian Ocean CHAPTER II. Arrival off Western Australia—King George's Sound—The town of Albany—Its streets and climate—Fort recently constructed at Albany—Freemantle as a port of call for mail steamers instead of Albany—Mr. Cobert and the discovery of coal—Departure of the train for Perth—Hotel accommodation and social life in Albany CHAPTER III. The Hon. J. A. Wright of the Southern Railway—The journey from Albany to Perth—The Great Southern Railway—Description of the line and country through which it passes—The Australian bush—"Ring-barking"—The Eucalyptus gum-tree—Chinese labour—Aborigines—Mr. Piesse's farm at Katanning—A drive in the bush—Arrival at Beverley—The Government line from Beverley to Perth—The city of Perth. CHAPTER IV. Description of Perth—Sir W. C. F. Robinson, G.C.M.G., Governor of the Colony—Hospitality in the city—The constitution of Western Australia—Local self-government—Legal luminaries in Perth—Hay Street—Prominent buildings—The Weld Club—Sanitation—Unfinished state of the city CHAPTER V. The Swan river—Government improvements—Excursion by steam-launch from Perth to Freemantle—Limestone quarries—Curious old wooden bridge near Freemantle—Mr. O'Connor's harbour scheme—Construction of the breakwaters—Firing a torpedo—A dredger brought from England to Freemantle—Banquet by the Press of Western Australia CHAPTER VI. The railway journey from Perth to Southern Cross—Scene at the railway station—Arrival at Southern Cross—The mail-coach—The coach journey to Coolgardie—Traffic and caravans en route—Water-supply in the Australian bush—Post stations—A night in a bush inn—The gold escort from Coolgardie—Police in Australia—"Spielers" or blackguards—A roadside letter-box—Exciting race into Coolgardie CHAPTER VII The Victoria Hotel at Coolgardie—Stores and shops in Bayley Street—Bustle and activity in the town—Lodgings and food—The "Bayley" Mine—"Reward Claims"—History of Bayley's find—The mineral wealth of Western Australia—The "dry-blower"—Groups of "chums" sinking prospecting shafts—The miner's life at Coolgardie—False rumours of "finds"—Bicycle-riding on the goldfields—The "Open Call" Stock Exchange—Amusements and drinking saloons in Coolgardie—Lack of water—Hay Street—Prominent buildings—The Weld Club—Sanitation—Unfinished state of the city CHAPTER VIII. Life in Coolgardie during the summer months—Description of the Hampton Plains Estate—Indigenous plants—Artesian water on the estate CHAPTER IX. The drive to Hannans from Coolgardie—Account of the Hannans mining camp—How to acquire a mining-lease—Cost of labour at the fields—A visit to the workings of the "Hannans Brownhill" and the "Great Boulder" gold mines CHAPTER X. Visit of Herr Schmeisser to "Hannans"—His opinion on the goldfields of Western Australia CHAPTER XI. The Kanowna or "White Feather" goldfield—The "Criterion" Hotel—Heavy machinery for the "White Feather"—Summary justice at the goldfields—Visit to the underground works of the "White Feather"—Mine fever—Demand for really experienced miners CHAPTER XII. A visit to Mount Margaret decided upon—Hiring of camels—Provisions for the journey—My camel man, Scott—The start from Hannans—First experience of Bush-life—A youthful prospector—The Credo Mine—Our camels stray to their old feeding-grounds—We stop at Kanowna for water—A "lake"—A slow and monotonous journey—Wild flowers in the bush—The mining township of Kurnalpi—Scott leaves our bread behind at the last camp—Travelling through the bush—Aborigines—"Condensers"—Accident to the buggy—The "Great Fingall Reefs" Mine CHAPTER XIII. Through the bush to Mount Margaret—Absence of rainfall—The "bell-bird"—Aborigines in the West Australian bush—Miners' indifference to sanitary precautions—Washing in the bush—Contention with Scott with reference to water—Mount Margaret in view CHAPTER XIV. Impressive appearance of Mount Margaret—The Mount Margaret Reward Claim Mine—Visit to Newman's Quartz Hill Mine—The "Great Jumbo" Claim—Return to "Mount Margaret"—Water ad lib. CHAPTER XV. Mr. Newman and I go to Menzies—"Niagara" Mining Camp—Hotel at Menzies—The principal mines—The "Friday" Mine—Water question in Menzies—The "Lady Shenton" Mine CHAPTER XVI. Coaching in Western Australia—The journey from Menzies to Coolgardie—Emus—At Coolgardie once more—The Londonderry Mine—Barrabin—Southern Cross—Progress of the Government railway—From Southern Cross to Guilford CHAPTER XVII. A few days' rest at Guilford—The journey to Cue, the capital of the Murchison district—The port of Geraldton—Mullowa—Water in the Colony of Western Australia—The townships of "Yalgoo" and "Mount Magnet"—The "Island" mining district—Sport in the Murchison district—Post-houses—The "Day Dawn" Mine—The town of Cue—Water-supply and hotels at Cue—Conclusion |

Appendix A [—Conditions under which Lands within Agricultural Areas are open for Selection.]

Appendix B [—Australian Trees.]

Appendix C [—Mining Rights.]

Appendix D [—Typhoid Fever in Australia.]

Albany

A Picturesque Bit of

Albany

The Bush

A Jarrah

Forest

Aborigines

View Near

Perth

St. George's Terrace,

Perth

Hay Street,

Perth

The Weld Club,

Perth

Hay Street,

Perth

St. George's Terrace,

Perth

Freemantle, from the

Sea

Freemantle

Harbour Works,

Freemantle

Firing a Torpedo, Freemantle

Harbour Works

The Dredger brought out from

England, Freemantle Harbour Works

Going for a

Ride

Dry-Blowers

The Open Call Exchange,

Coolgardie

Hannans

Stores for the

Camp

The Horse Whim, Hannans

Brownhill

The Printing and Publishing

Offices of the "Western Argus," Hannans

Herr

Schmeisser

Herr Schmeisser, Dr.

Vogelsang, and Mr. Wm. A. Mercer about to start on their Tour of

the Fields

Summary

Justice

Prospectors' Camp, Credo

Mine, Black Flag

In the Bush

In the Bush

Solitude

Aborigines

Aborigines

Returning from Work: A Sketch

at the "Friday" Mine

Miners' Camp, Lady Shenton

Mine

An Awkward

Moment

Prospectors

Barrabin

View near

Guilford

On the Quay,

Geraldton

A Camel Team

Day Dawn Mine

Cue

A Mining

Township—Murchison District

A Hot Night in the Red

Sea.—The Saloon Deck of the "Oceana"

Perth

Menu

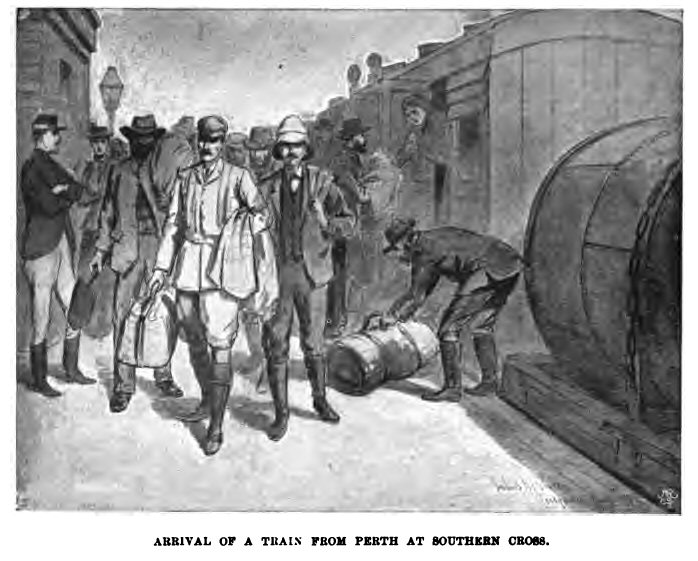

Arrival of a Train from

Perth at Southern Cross

On the Road to

Coolgardie

Bayley Street,

Coolgardie

A Dry-Blower

The "Homestead," Hampton

Plains

Pioneers of

Civilisation

Main Shaft, Great Boulder

Mine

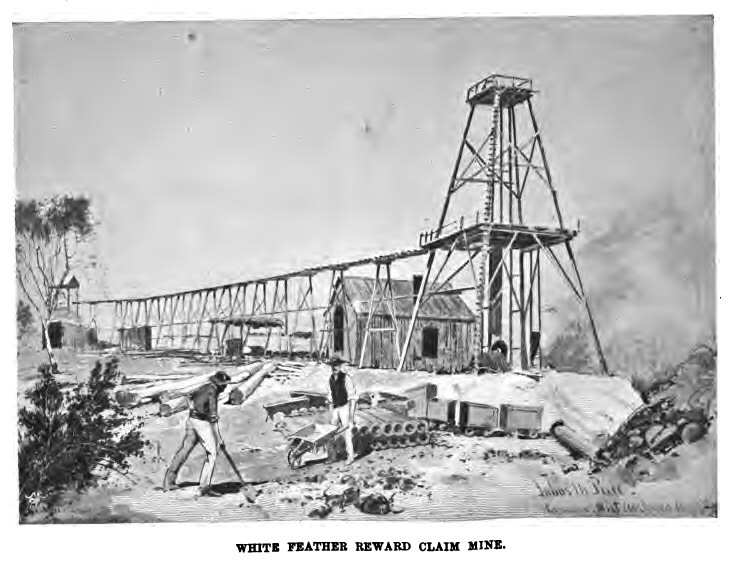

White Feather Reward Claim

Mine

Home Life in a Bush

Township. An Evening Scene

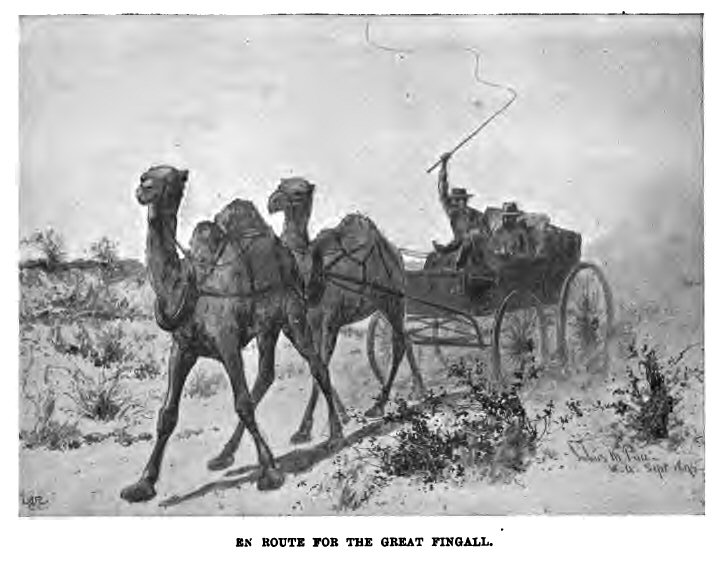

En Route for the Great

Fingall

My Caravan in the

Bush

A Condenser

Mount Margaret Reward Claim

Mine

Police Bringing in Native

Prisoners from an Outlying District

Putting up a

Battery

A Post-House on the Road to

Cue

The Departure of the

Mail-Coach, Cue

Western Australia, 1895 [not available.]

THE LAND OF GOLD.

Ocean travelling of to-day—A visit to Western Australia decided upon—My outfit—The voyage on board the Oceana—Gibraltar—Suez—Aden—Colombo—The Indian Ocean.

A voyage to Australia nowadays is so ordinary an occurrence that it would be supererogatory to attempt to make "copy" out of what must be the usual experiences of the "traveller" by any of the palatial steamers which seem to connect even the nethermost ends of the earth. Ocean travel has been so much improved during the last forty years, that a run out to the Antipodes is rather in the nature of a pleasant excursion than a tedious journey. Very different indeed is such a trip as compared with the voyages made by the sailing ships of the sixties, when the only possibility of enlivenment lay in the offchance of going down with all hands on board.

In spite of the attractions of an unusually gay London season, the opportunity which presented itself of a journey across the solitudes of Western Australia was one not to be missed, more especially as such an expedition had long been one of my pet ideas; for this particular part of the world, forming though it does so important a section of Her Majesty's colonies, is still to a great extent a terra incognita, and I imagined must offer to those in search of adventure exceptional opportunities for gratifying their tastes. How little is really known of these distant regions one can scarcely conceive, and it is only with the greatest difficulty that any reliable information can be obtained as to the country, the climate, or the equipment necessary for such an expedition.

From Albany on the coast, to Perth the capital, and thence to the goldfields, I need scarcely say is all plain sailing; but, as to the comparatively wild regions beyond, nothing of any definite nature could be ascertained. By dint, however, of much inquiry, and with the assistance of an old squatter, I got together an outfit which seemed well adapted to meet any emergency, and it may be of interest at this point, to describe the items which go to make up the regulation outfit ? la Silver & Co. for the goldfields. They were briefly as follows: a very light canvas tent with large double fly roof fitted with mosquito net lining, a portable folding table, lantern, canvas bath and bucket, and the usual ground sheets and other paraphernalia; one of Poore's American cooking-stoves (similar to one I had used in the Gobi desert, and which had then proved invaluable) fitted with a complete set of cooking and table requisites, and some camel-hair rugs and cork mattresses. Then there was also my wardrobe, which was contained in soft leather mule pack valises, and consisted of a complete outfit from white ducks, karki suit and terrai hat, and the thickest homespun underclothing, mosquito net head-dress, goggles, thick brown shooting boots and canvas leggings. To these were added a compass, an aneroid barometer, a reliable revolver, a twelve-bore breechloading gun, and last, but not least, a carefully thought out medicine-chest, fitted up by Burroughs & Wellcome with their excellent drugs in tabloid form. This, with a Kodak camera, and painting and sketching materials, practically completed my equipment.

At the time of writing, when the expedition is over, the mere perusal of this list is enough to fill one with laughter, for one was not very long up country before realising that the greater part of this imposing outfit was sheer impedimenta. In fact I never had any occasion to use one-half the articles I have enumerated. Such an equipment might perhaps be needed if one was making an exploring expedition from the coast right away to the interior. On a journey to the goldfields, by the route I am about to describe, nothing of this elaborate description is needed; but the popular impression, amongst London outfitters, seems to be that a man going out to the "fields" should rig himself out like a Christmas-tree. For the benefit of "new chums" intending to visit these parts, I would recommend, as the result of my experience, the taking of as little, as possible. An extra pair of trousers, two flannel shirts, some handkerchiefs and socks, and a few familiar drugs, for even a long trip, is all that is necessary, and can be easily packed up with one's blanket, rug and waterproof sheets in what is known as one's "swag"—a canvas valise—and which can be purchased in Perth for a few shillings. A good possum rug can also be had for about four or five pounds, together with the indispensable bush requisites, such as water-bags, knives and forks, mugs, etc., and are cheaper in Perth than in London. It is astonishing to the newcomer up country to see what a lot the practical bushmen can pack away in their "swags," and which can be thrown on a coach or slung across the back of a camel without fear of injury to their contents. Tents and cooking-stoves are unnecessary in the bush, where the climate is always equable enough for sleeping out in the open, though it is somewhat cold during the winter nights, while fuel is to be had everywhere in abundance. Tents, guns, medicine-chests, and the other paraphernalia mentioned above, are useless encumbrances unless one proposes living some months in the bush, and making a permanent encampment.

The voyage out was nothing less than a delightful holiday. Indeed, how could it be otherwise in such a ship as the Oceana, and with so charming a commander as Captain Stewart? I was also lucky enough to meet with several kindred spirits on board, and the long voyage seemed but a brief trip.

A HOT NIGHT IN THE RED SEA—THE SALOON DECK OF THE

"OCEANA."

A peep in at Gibraltar, giving time for a drive round and for obtaining a rough idea of that wonderful fortification, a few hours on shore in Malta; then on to sleepy Brindisi, and, from there, an exhilarating run down to the Greek coast and across the blue Mediterranean to busy Port Said, "the home of the riff-raff and the donkey-boy;" thence on through the canal, a truly wonderfully weird voyage on a moonlight night, with the deadly stillness of the vast desert hemming one in on either side. Passing Ismailia, in the early glow of the Egyptian morning, looking like some huge painting in the still air against the brightening sky, then on to Suez, where only a very short stay is made, then through the Red Sea, and a few hours on shore at Aden, with a run up to "camp" and a hasty peep at the picturesque native village, then across the Indian Ocean. After this, a nasty bit of monsoon weather to Colombo, where a whole day is spent in the midst of its tropical surroundings, all combine to make the time pass rapidly enough. After leaving Colombo, the voyage is one of absolutely unbroken monotony. Ten days of sky and sea. Until the line is passed, the heat is intense, though occasionally tempered by a breath from the monsoon. Then, as we run away from the sun a very noticeable change in the temperature becomes perceptible, for we are approaching the Antipodean winter, which, though never so severe as our own at home, still presents a very marked contrast to the tropical heat we so recently experienced. This, together with the rapidly shortening days, and the increasing cold, grey aspect of the sea and sky, all help to denote that we are running into mid-winter, and rapidly approaching our journey's end.

Arrival off Western Australia—King George's Sound—The town of Albany—Its streets and climate—Fort recently constructed at Albany—Freemantle as a port of call for mail steamers instead of Albany—Mr. Cobert and the discovery of coal—Departure of the train for Perth—Hotel accommodation and social life in Albany.

The first glimpse of the coast of Western Australia, as obtained in the cold grey light of a winter morning, is somewhat depressing, and standing shivering on the damp deck one finds oneself regretting the lovely summer weather one had so recently experienced. Even as the land is gradually approached its aspect improves but slightly, for the bleak, desolate-looking coast-line is of an uniform and almost unbroken brownish grey tint, which is in great contrast to one's recollections of the brilliant tropical scenery of Ceylon. Once, however, past Cape Lewin, as King George's Sound is reached, and as the rising sun gradually sheds a golden hue on the rugged expanse of precipitous bush-covered headlands, the effect for a few minutes strangely recalls parts of far-away England, but the illusion is only momentary. As far as the eye can see there is no sign of human handiwork, nothing to break the perennial solitude which appears to reign over the land. It seems a pity that these fine bays, forming such splendid natural harbours, and the so long deserted shores, should still be waiting for the busy crowds which must some day awaken them. More especially does one feel this when one recollects how over populated are other parts of the world.

Steaming steadily down the coast we at length sight the headland known as Cape Vancouver, at the entrance to King George's Sound. Here the coast-line, receding rapidly, forms a magnificent natural harbour, opening out of which, through a narrow entrance, is the beautiful land-locked bay known as Princess Royal Harbour, on the northern shore of which nestles the picturesque little town of Albany, and opposite which we drop anchor. It is difficult to realise that five weeks have elapsed since we left Gravesend. The time has indeed slipped away with incredible rapidity, and one feels more than reluctant to leave the home-like comforts and genial companionship of the Oceana for the "roughing-it" which we know is in store for us.

On a nearer inspection the little town of Albany improves considerably, for it has a somewhat scattered appearance as seen from the bay, but this effect is dispelled on landing. Its well-planned streets, though yet in the most embryo condition, promise to look remarkably well when (if ever) completed, for most of them have a background of rocky and well-wooded hills, which gives a very picturesque aspect to the place, whilst the luxuriant, semi-tropical vegetation to be seen everywhere, combined with the delightful aroma of the burning of gum-tree wood, impart a sense of repose which is particularly refreshing after the continual movement of ship-board life. A short walk through the town soon, however, reveals the fact that energy is not one of the salient virtues of its inhabitants, for it would be difficult to imagine anything more inert than the aspect of the streets. This impression is well founded, for, from what I learnt, it appears that the people only rouse themselves into activity on the arrival of the different steamers which call in here, and as soon as these have departed they lapse again into their usual state of somnolence, which seems to thoroughly justify the cognomen of "Sleepy Hollow," which was once given to the place. This condition of things certainly does not augur well for the rapid development of the town, and strikes even the most casual of observers as a pity, for Albany ought to become a place of some importance in the colony. Its climatic conditions and other advantages combine to make it a kind of natural sanatorium. It could, therefore, be easily developed into a charming watering-place, which would, sooner or later, prove a boon to the inhabitants of the neighbouring bush townships. Apart from these peaceful attributes, Albany is a strategic point which has always been regarded as of the utmost importance in all schemes of Australian federal defence, while the value of its harbour, as a port of refuge or a coaling-station to the whole of Australia in the event of a war, cannot be overestimated. That this has not been overlooked is proved by the fact that the defence of the harbour has been jointly undertaken by the Imperial and Australian Governments, acting on the recommendation of the Committee of Commandants, which met in Albany in November, 1890.

The fort, recently constructed, and which commands the entrance to the Sound, consists of three batteries armed with three 6-inch R.B.L. guns, mounted en barbette, and six 9-pounder field guns for the defence of the mine fields. These guns, which were a present to the Colony from the mother country, arrived from England in March, 1893. The garrison of this small though important stronghold consists of a company of garrison artillery from South Australia, with a nominal strength of thirty of all ranks, under the command of an artillery officer, nominated by the Imperial war office. It appears a ridiculously insignificant force in comparison with the importance of the position. The inertia of the inhabitants possibly accounts, to a great extent, also, for the slow developments in this direction, the cost of living in Albany being so high that any augmentation of the garrison at the fort would mean a large increase of annual expenditure. Otherwise, the position would probably be utilised as a good training-ground for the entire artillery force of the Colonies, with much advantage. Whilst, however, to a very great extent the want of energy noticeable in Albany is attributable to the climate, which is certainly enervating, there are other causes which may have in no small degree contributed to this state of affairs. It is not difficult to arrive at the real cause which, in a few words, may be said to be the Government scheme for making Freemantle the port of call for all the mail steamers. If this ever became an established fact it would sap the vitality of the south-western portion of the Colony to a great extent, and Albany is the chief town. The motion which was proposed by the Premier, Sir John Forrest, at the postal conference in Hobart this year, "That so soon as Freemantle be made a safe and commodious harbour that the mail steamers be compelled to make it their port of call instead of Albany," produced quite a panic in the little town. Against this, however, there seems every probability of coal being found in close proximity to King George's Sound. If this be true, and judging from the opinion of experts there seems little doubt of it, it would completely revolutionise the entire shipping trade of the whole of Australia, for Albany is the first Australian port of call for vessels coming from Europe, and the last port for vessels leaving Australia. Consequently, the greater portion of cargo steamers could call at Albany, and the economy that would be effected by avoiding coaling at that most extravagant of stations, Colombo, would naturally, to a large extent, influence the movements of a trade which is yearly on the increase. Albany, I learnt, owes a deep debt of gratitude to a Mr. Cobert, a practical coal-mining expert, for his persistent efforts towards a realisation of this scheme. For some years past he has been working incessantly to discover the best locality in which to open the first mine. Realising the vast importance of such a discovery, the Government have at length come to the assistance of Mr. Cobert by lending him a boring machine, and supplying funds to test thoroughly the value of this portion of the Colony from a coal-mining point of view. If there should prove to be any future in this respect for Albany it will also in a great measure be due to the persistent enterprise of the Great Southern Railway Company, as the district through which their line passes contains some of the best agricultural land in the Colony. This line, it may be of interest to mention, is the first constructed on the "Land Grant" principle, the Company having received 12,000 acres of land for each mile of rails laid. When one learns that the line is 243 miles in length, the area of country the Company holds amounts almost to a principality.

One of the chief events of the week in Albany is the departure of the train with the English and Colonial mails and passengers, on Sunday evening, for the capital of the Colony, Perth. If the weather be fine, at five o'clock, the hour of leaving, the station platform presents a most animated appearance, being converted for the nonce into a sort of promenade where all the town folk meet to discuss the events of the week and criticise the new arrivals. This weekly event, since the discovery of the goldfields and the consequent influx of travellers, has assumed a proportion which taxes the capacity of the station to its utmost, and could hardly have been contemplated by the most sanguine of optimists when the line was first started.

Hotel accommodation is not one of the strong features of Albany when one considers it is, so to speak, the front door of the Colony. I was, however, given to understand that I should look back even upon this as a little paradise compared to what I should have to put up with up country.

Social life in the tiny township is naturally limited, considering its inhabitants scarcely number three thousand. There are several charming families who seem to know how to make the best of life, spent though it may be in so remote a corner of the earth. That latest of latter-day institutions, the Club, without which no community of Englishmen can be considered complete, is here a most well-appointed institution whose members thoroughly uphold the West Australian traditions of hospitality to the strangers within their gates.

The Hon. J. A. Wright, of the Southern Railway—The journey from Albany to Perth—The Great Southern Railway—Description of the line and country through which it passes—The Australian bash—"Ring-barking"—The Eucalyptus gum-tree—Chinese labour—Aborigines—Mr. Piesse's farm at Katanning—A drive into the bush—Arrival at Beverley—The Government line from Beverley to Perth—The city of Perth.

I found that a few days in Albany were more than sufficient. One could see all there was to see in a very few hours. On learning of my approaching departure from Perth, the courteous managing director of the Southern Railway, the Hon. J. A. Wright, placed his private saloon carriage at my disposal, and offered to accompany me on what he jocularly termed "a personally conducted tour up the line." As the result of my accepting his kindness the whole journey proved to be a sort of delightful excursion, for Mr. Wright possesses an inexhaustible fund of good nature together with the very keenest perception of humour, and, with his unfailing store of amusing reminiscences and anecdotes, it may be imagined that there was no time for a dull moment in his comfortable "car." To Cook or Gaze such a guide would be invaluable indeed!

The journey from Albany to Perth is not impressive, as far as speed is concerned, for in travelling a distance of 330 miles the train takes up about sixteen hours—which is not what may be considered dangerously rapid travelling. Still it must be remembered that high speed is never a feature of Colonial traffic.

Several prolonged stoppages in the case of the ordinary train have to be made en route for meals and other apparently important matters, which seem mostly to consist of experiments in shunting. So the average rate all through never amounts to more than twenty-three miles in an hour—which is nice quiet travelling, and gives one ample time to appreciate the scenery on either side. In my own case, however, I thoroughly enjoyed the novelty of being able to stop the train, which consisted of the saloon car and the luggage brake, at my own sweet will, and on several occasions I took advantage of my privilege either for the purpose of making a sketch or of taking a snapshot.

The line of the Great Southern Railway ends at a place called Beverley, some 242 miles from Albany, where it joins the Government railway from Freemantle to Perth. The rails are laid on a 3' 6" gauge, and the carriages and all the rolling-stock are on an equally small scale. Many of the carriages are built in America, although a good many of them are brought over in sections from England.

The country through which we passed was more than monotonous: dense flat wastes of forest and bush lay on either side, though the many miles of this dreary wilderness were occasionally lightened by extensive clearings or even by patches of cultivation, betokening the presence of the enterprising settler. When these oases were seen they made one recollect that the country was neglected not because it was deemed unworthy of cultivation, but simply because man has yet to learn its value.

Land, in this part of the colony, is absurdly cheap, and even along the line of railway there are still thousands and thousands of acres for sale, at the nominal figure of from 10s. to ?1 per acre, according to the density of the timber and bush on them, that requiring least clearing fetching the higher figure.

The purchase money is payable in instalments covering a period of twenty years, subject to certain restrictions, such as compulsory living on the property, fencing it in, and generally improving it within certain fixed periods after possession is taken. The conditions did not, however, strike me as onerous.*

[* See Appendix A.]

The great difficulty new settlers have to contend with out here is that of getting labour at anything like reasonable rates, the ordinary farm hand or common labourer having an exorbitant idea of his own value. The "working man" who, in England, would earn 18s. a week demands, the moment he sets foot in Western Australia, a weekly salary of three or four times the amount, and is indeed from all accounts the curse of the Colony.

On one or two stations we passed Chinese labour had been used, not only to great advantage, but with considerable gain on the score of economy, and, from what I gathered, the general idea of landowners out here is that the employment of a large number of the industrial Celestials would help considerably to, open up and push forward the development of the Colony. Political motives, however, generally stand in the way of any employment of Chinese on a large scale—for many of the capitalist class of settlers have seats in the Parliament at Perth which they do not care to jeopardise. Meanwhile this magnificent country, with a line of railway to feed it, is lying idle in consequence, in most cases, of the dearth of cheap labour.*

[* See Appendix B.]

There are few stopping-places of any importance for some distance from Albany—most of the railway stations having sprung into existence since the Great Southern Railway was opened for traffic, and though many of them have high-sounding names, a few shanties and occasionally a "bush store" are what they generally consist of.

What chiefly strikes one in this solitude is the utter absence of human or animal life everywhere, not even so much as a bird is ever visible to break the eternal monotony. The aborigines themselves, to whom in the past these wilds were perhaps a happy hunting-ground, have long since departed, or are dying out so rapidly in obedience to some unaccountable law of nature, that in a couple of generations probably not one of them will remain. All, in fact, appears to point to a sort of intermediate or waiting stage. Nature is as though expecting the approach of the white man for the awakening from her long sleep.

With regard to the aborigines, Mr. Wright told me two amusing incidents of the effect the opening of the railway had on the natives. They assembled at many points in order to examine the new mystery, and all agreed that there was something very uncanny about the train because it left no sign of a track, and on seeing the telegraph wires on both sides of the line they expressed their opinion that it was a d———bad fence, because anybody could get under it!

We stopped at a rising little place named Katanning for the night, our saloon carriage, in which we were to sleep, being shunted into a goods shed. A capital supper at the station "hotel" (which by the way was lighted by electricity) and a stroll through the village finished up an exceedingly pleasant and interesting day.

As I was not to continue my journey to Perth till the evening, my host suggested a drive into the bush during the afternoon, and my taking a gun on the chance of a shot at a kangaroo, a suggestion which I cordially accepted. A few tamar, a sort of kangaroo hare, were, however, the only result of the expedition though a charming drive through the wildest of forest scenery imaginable amply compensated for the poorness of the sport. When the time came for departure it was certainly with feelings of regret I left the little township in which I had spent so pleasant a time.

In the early hours of the morning we reached Beverley, the terminus of the Great Southern Railway, and I was awakened by a series of shunting, or rather bumping, manoeuvres, through which our carriage particularly seemed to be undergoing. For fully half-an-hour this interesting operation lasted, though what the result of it was, except to effectually wake us up at five o'clock in the morning, could not be ascertained as we found ourselves when it was over within a few yards of our point of departure. The bumping was, I afterwards found, caused by the colonial system of loose coupling; the detrimental effect of such a method on rolling stock should be obvious, though the colonial mind has not yet grasped the fact. The Government line from Beverley to Perth, a distance of some hundred miles, is certainly the most curious specimen of railway engineering it has ever been my luck to travel over. Having been laid as cheaply as possible, from start to finish it is quite a series of surprises, which are more interesting to read about than to experience. To describe it as constructed on the "switchback" principle would be to put it mildly, for when laying it no attempt whatever was made to overcome any physical difficulties the country presented, with the result that the rail runs uphill and down dale without any attention to gradients and other such trifles. Cuttings are unknown quantities, and although a high range of hills, the "Darling" had to be crossed, there was no such a thing as a tunnel anywhere. Standing on the platform of the car looking back along the line, the effect is most extraordinary, and one wonders how any engine can be built to stand such terrific work; and as to the curses, well, I had never before believed the story of the new engine-driver, somewhere in South America, who pulled up in great alarm because he saw some lights in front of him which proved, however, to be the rear lights of his own train; but this bit of line could almost give that one points and win easily. Feeling oneself tearing at full speed down the steepest gradients (many of them I noticed were as much as one in thirty) was most exciting, and it was often a wonder to me that the train did not run away with the engine. That accidents have not been of frequent occurrence is more a matter of good luck than anything else. An amusing anecdote was told me of an English engineer who was being shown this line, and was allowed to travel on the locomotive. The movements of the driver as he deftly manipulated the brake at each variation of the innumerable grades appeared to interest him even more than the actual line. After watching the man intently for some time he suddenly remarked with enthusiasm, "Why this man is not an engine-driver, but an artist!" This sensational line I learn is shortly to be abandoned, as the Government have in progress a "deviation" which will to a great extent do away with this "picturesque route."

A bend in the line at last brought us in view of the city of Perth, with its many fine buildings standing out in white relief against its background of foliage, and looking singularly oriental in the clear antipodean atmosphere, whilst the beautiful river winding through the valley at our feet, and on which this fair city stands, lent an additional charm to the scene.

In a few minutes the train glided into a large and handsome station, the platform of which was thronged with a busy crowd of people, and I found I was in the capital of Western Australia.

Description of Perth—Sir W. C. F. Robinson, G.C.M.G., Governor of the Colony—Hospitality in the city—The constitution of Western Australia—Local self-government—Legal luminaries in Perth—Hay Street—Prominent Buildings—The Weld Club—Sanitation—Unfinished state of the City.

It would be difficult to imagine a more pleasant or more picturesquely situated city than the capital of Western Australia, and the most casual stroll through its broad streets or along its beautiful riverside drive is sufficiently convincing proof that it has not been designated "the fair city of Perth" without reason. When the building of the place is complete it will vie with any other city of Australia, for at present Perth, through untoward circumstances, is somewhat behindhand. Events in Western Australia have not shaped themselves quickly or definitely as in the other colonies where cattle-rearing, sheep-farming, or agriculture have for many years past represented huge and growing industries. This may therefore, to a certain extent, account for the somewhat backward state of affairs which has existed in this city till almost recently, otherwise it is difficult to explain how so important a place, the foundation stone of which was laid as far back as 1889, should still look unfinished and number so small a population as 12,429, which in proportion to its area of 3850 acres is certainly insignificant. Other parts of Australia owe their present vitality in a great measure to the discovery of gold, and so it will undoubtedly be with Western Australia, and Perth, will, as the centre of the Colony, be the first to benefit by this marvellous influx of good fortune in the shape of her goldfields; and the discovery of Coolgardie will undoubtedly in future years be looked upon as the stepping-stone of Western Australia's era of prosperity. Already the effect it has had on the quiet steady-plodding townsfolk is remarkable; they seem, one and all, to have suddenly awakened to the fact that to make hay while the sun shines is an excellent axiom, and that now or never is the opportunity. As the result of this advent of eager crowds of prospectors, miners, and others on their way to the goldfields, and who are forced to make a halt before passing Perth, on all sides is now heard the hammer of the carpenter and the trowel of the bricklayer, whilst houses and stores are rising as if by magic. It must not, however, be inferred from this that Perth as a city dates from the discovery of the goldfields. For some years past under the able management of its local authorities it has gradually been rising into a condition befitting the capital of the Colony, so the sudden advent of good fortune has not found it altogether unprepared for so lucky an emergency. It is now more than four years since the responsible Government of the Colony was inaugurated by Sir W. C. F. Robinson, G.C.M.G. His excellency, who had twice held the governorship of the Colony, was entrusted with the responsible task of starting it off on its new career, since which auspicious occasion there has been shown no lack of energy by the Government for the time being in power. All their proceedings have been marked by a despatch and energy which speak well for the prosperity of the country and have met with general approval. Public works and schemes, many of them of the greatest utilitarian value, have been so constantly on the tapis that the spacious Government offices have proved almost too small to house the increasing army of officials and draughtsmen. In fact, had the population increased in proportion to the energy manifested by the Government, there can be no doubt but that Perth would now be among the most populous of Australian cities.

Nevertheless, in spite of the somewhat intermediate stage through which Perth, in common with all other cities in Western Australia, is passing, it is an agreeable place in which to spend a few days; and although there is not yet the bustle and activity or the gaiety of large cities, there is still a certain amount of life about it which makes the time roll by very pleasantly. That most characteristic of Australian virtues—hospitality—is here lavished with an open-handedness which makes the new arrival feel at once at his ease, and quite dispels any preconceived ideas he may have had as to the value of a letter of introduction; not, however, that "form" is in any way dispensed with. In fact, this excessive formality is particularly striking to the newcomer from the mother country, especially when he realises that the entire population of the whole Colony does not amount to that of a small English provincial town (say about the size of Brighton), whilst the inhabitants of the capital are not equal in numbers to those of Herne Bay. Indeed, one is not long in the place before discovering that etiquette with all its conventionalities is observed at Perth with a regard to the smallest minutiae which is almost droll in its seriousness. Loyalty to the "old country" is here displayed in quite as marked a degree as in the sister colonies. The way in which "Society" circles round the Government House proves a regard for "tradition" which is from all accounts so great a characteristic of other parts of Australia. The receptions of the Administrator and Lady Onslow are in a comparative degree as high social functions as any given by the Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland. All the luncheon or dinner parties of leaders of the Government, whilst Parliament is sitting, are of the most orthodox official character, and would not reflect discredit on Downing Street itself. The kindness and hospitality which were shown me by that most genial of premiers, Sir John Forrest and his charming wife, as well as by Sir George Shenton, the Speaker of the House, the Hon. H. J. Saunders, Mr. Wm. A. Mercer and others, will long remain in my memory as amongst the most delightful reminiscences of my Australian visit.

It may be of interest here to give a slight idea of the Constitution of Western Australia, in order to explain to a certain degree the extraordinary amount of officialism which rules in the capital and which seems to pervade all classes; for at every step one seems to come in contact with the minister for this or commissioner for that, till one at length wonders whether they are all officials, as in the case of the South American state where, to avoid jealousies, the army consists entirely of officers! The Government of the Colony is vested in the Governor, who is appointed by the Crown—and who acts under the advice of a Cabinet composed of five Ministers. The Executive Council, which consists of the Governor, the Colonial Secretary, the Attorney-General, the Colonial Treasurer, the Commissioner of Crown Lands, the Commissioner of Railways, the Director of Public Works, and the Minister for Mines. The Parliament is composed of two Houses—the Legislative Council and the Legislative Assembly. The Colony is represented in the Council or "Upper House" by twenty-one members, or three for each electoral province, whilst in the Assembly it returns thirty-three members representing so many electorates. When therefore it is remembered that the entire population of Western Australia at the end of 1893 was only 65,064, it cannot be said that the electors are poorly represented at the seat of Government. As a matter of fact the way the seats are distributed affords some material for astonishment. For instance, the capital, with 9617 inhabitants, has no less than three members; Freemantle, with 7077, has the same number; whilst the entire goldfields district, with a population roughly computed at 25,000, has only two representatives. Two other districts, East Kimberley and Gascoyne, with an electoral roll of twenty-six and twenty-four respectively, are each represented by a member. The comparative calculation which resulted in this remarkable distribution of seats is somewhat incomprehensible to the ordinary mind. It may be argued that the enormous tracts of country so sparsely populated and the consequent distance to be traversed render it necessary for arrangement, but the proportion of 2 to 25,000, as against 3 to 9617, is certainly confusing.

Local self-government also exists in most of the principal townships, the power to declare any town a municipality being vested in the Governor. The number of councillors for each town varies according to the population. Where it is less than one thousand it is six; over one thousand and less than five, nine; over five thousand, twelve; exclusive in each case of the chairman. Apart from these municipalities there are also district road boards, which are appointed to represent the several road districts into which the Colony is divided, and which are defined or altered at any time at the option of the Government.

The majesty of the law in Perth is well represented by quite a big array of legal luminaries, whilst the requirements of the city are looked after by the corporation, which is presided over by a mayor.

It will be seen, therefore, that everything is ready in Western Australia in the way of government for the population which has been so slow in arriving.

The principal business thoroughfare, Hay Street, is not at present an imposing one, being fur too narrow, consisting, as it mainly does, of a succession of small buildings of mean elevation and no distinctive pretensions. There are here and there a few more imposing structures, which, however, only seem to show up the remainder in strong contrast. The public and other buildings are, in many cases, worthy of remark. On St. George's Terrace—a really handsome thoroughfare—are several fine structures which would be considered good specimens of architecture in any city. Prominent among these are the Post-office, a large block of buildings forming one wing of the Government Offices—the offices of the Union Bank of Australia; the National Bank of Australasia; the Mutual Provident Society and the National Mutual Life Association of Australasia—whilst hidden in a mass of semi-tropical vegetation and surrounding well-kept grounds stands Government House, a large stone edifice of Gothic design and most picturesque appearance.

Here, as elsewhere, club-life is one of the chief social institutions, and the Weld Clubhouse, where, through the courtesy of its members, I was provided with comfortable quarters, has been recently erected on a beautiful site overlooking the town, and is, in my opinion, the finest architectural achievement in the city; whilst it is also certainly one of the best organised and managed clubs I was ever in anywhere. It reminded me very much of that most perfect institution at Shanghai, the staff, which, curiously enough, is composed entirely of Chinamen, completing the resemblance.

The rush to the goldfields, and the consequent rapid increase of population in the capital, has also had the effect of attracting the attention of British speculators to Perth, several big syndicates having acquired valuable leases, on which building operations are in full swing, and which promise fine results.

The city is plentifully supplied with pure water by the Perth Waterworks Company, who have a reservoir seventeen miles distant in the Darling Hills. The sanitary conditions of the district are in the hands of a local board of health, so the city is in as healthy a state as is possible, and the death rate from all causes remarkably low. The Government Hospital, which is looked after by a competent staff of medical men, though not quite up to the requirements of the city, has nevertheless considerably helped to further this beneficent state of affairs. A new building is shortly to be erected.

The designs for a theatre are being prepared; for hitherto professional histrionic art, as represented by travelling companies, has only found a temporary home in the town-hall or other convenient, or rather inconvenient, spot. That such an undertaking will prove a success need scarcely be doubted if good entertainments are provided; for I learn from a resident that one company, in 1891, netted ?1000 in a stay of ten weeks, which might reasonably be considered fairly "good business" for the Colony.

There remains, however, a great deal yet to be done before the city itself can be considered finished. The busy tramways, the cable cars, the electric light, all the advantages in fact which are considered absolutely indispensable in the most mushroom of American townships, are here conspicuously absent. Beyond a few dilapidated hansom cabs which ply for hire at ruinous fares, there is absolutely no means of locomotion from one end of the town to the other. An energetic man with a couple of omnibuses would have the road to himself. But such an individual until just recently was quite an unknown quantity in Perth. On dark nights a few gas jets and the oil lamps in the different stores axe all that illumine the surroundings. When, however, there is a moon the gas is dispensed with, on the score of its expense. With so unlimited a supply of fuel as the surrounding bush offers, electric lighting ought to be so cheap as to be within the means of all classes, and in towns so largely built of wood as are those of Western Australia ought to be made the only legal illuminant. One or two big blazes will, however, be the necessary misfortunes in order to open the eyes of the authorities to the advisability of this reform in the lighting. In America they have bad many severe experiences to teach them this lesson, with the result that the electric light is often brought in when the township is first planned. All these, as well as many other adjuncts to a thriving centre, promise, however, so I learnt, to soon become accomplished facts; and the next few years ought to see Perth amongst the handsomest and most thriving cities in Australia.

The Swan River—Government improvements—Excursion by steam launch from Perth to Freemantle—Limestone quarries—Curious old wooden bridge near Freemantle—Mr. O'Connor's Harbour scheme—Construction of the breakwaters—Firing a torpedo—A Dredger brought from England to Freemantle—Banquet by the Press of Western Australia.

"The chief port of the Colony," as Freemantle is usually, though somewhat prematurely, designated, has a population of rather over eight thousand, and is situated at the mouth of the Swan Eiver, about twelve miles west-south-west of Perth, with which it is connected by road, railway, river, telegraph and telephone.

Though as yet only a "harbour" in name, the extensive improvements now being carried out by the Government to widen and deepen the estuary of the river, promise, when finished, to give it a firm foothold in the favour of the captains of the various ships which trade up the western coast, although much more important results are anticipated in return for the vast expenditure the scheme will necessitate. Learning of my desire to inspect the works of which I had heard so much since my arrival in the Colony, the Government courteously placed their steam launch at my disposal, so one afternoon, accompanied by Mr. Dillon Bell, the engineer in charge of the works, and a small party of journalistic friends, a delightful excursion was made. The weather was as perfect as could be desired, and in the bright Australian sunshine with the river's banks clothed in their perennial verdure it was hard to realise that we were still in the antipodean midwinter. Between Perth and its seaport are many beautiful riverside suburbs, where, during the almost tropical heat of the summer, those fortunate enough to be able to afford the luxury can find cool retreats after business hours in the city. Claremount, Peppermint Grove, Cottlesloe, and other villages nestling among the trees, were pointed out as we steamed past on the placid water. A brief stoppage was made at a place called Rocky Bay, a short distance before reaching our destination, to afford an opportunity for visiting the quarries from which the limestone for the two projected breakwaters is being extracted. The scene was a busy and animated one, and amply demonstrated that the Government, having decided to make Freemantle the big seaport of the Colony, were neglecting nothing on the score of energy in the carrying out of the scheme. Quite a small army of labourers were hard at work quarrying and blasting out the stone, which was hoisted on to hopper-trucks by four large steam cranes, and when a sufficient number of the trucks were filled they were immediately taken down the line by railway engines and "tipped" on to the breakwater, many hundreds of tons of stone being thus deposited every day. Even at this rate several years would elapse before the two breakwaters would be finished, to say nothing of the rest of the harbour works.

After a stroll round, the launch was joined again at a spot some little distance further down the river, when a few minutes' steaming brought us in view of the town of Freemantle. Here we passed under a curious old wooden bridge, built of the famous Jarrah wood, some thirty years ago, by convict labour. Although exposed to the action of wind and weather for so many years, the structure, which resembled some huge centipede in its bare nakedness of outline, appeared in no way deteriorated, and I was informed that not a flaw had been detected in it since the day it was built. Just beyond the bridge the river gives a bend, and we came in sight of the broad expanse of water which it is proposed to convert into a spacious harbour. A few hundred yards beyond, the breakers of the Indian Ocean rolled in majestically till arrested in their progress by the bar of rock which extends across the mouth of the river. The scene was a strikingly interesting one, and rendered the more so to me on account of the many controversial opinions I had heard expressed as to the practicability of the works before me. The scheme, which is being carried out, was designed by the engineer-in-chief of the Colony, Mr. C. O'Connor, a gentleman who has had much experience in New Zealand in the matter of harbour construction. His scheme, roughly speaking, is to afford protection to shipping alongside the existing jetty, which is to be considerably extended; to protect the mouth of the river, the bar across which he proposes to remove in order to deepen the estuary; and, for some distance up on either side, to reclaim sufficient of the shallow water for conversion into wharves, docks, etc. For this purpose his idea is primarily to construct two breakwaters from the heads at either side of the mouth of the River Swan, and, whilst these are in course of construction, to remove by dredging and blasting the reef which has hitherto impeded free entry from the sea to the river.

The work was commenced some three years ago, and the magnitude of the undertaking could, to some extent, be appreciated when it was seen how little, comparatively, had been done in the time. As we crossed the bar the water was so shallow that at one point our little launch actually grated over the rocky bottom, and this gave us a fair idea of the amount of work to be accomplished before the harbour will "afford safe and commodious accommodation to the largest ocean-going steamers"—as the official description of the scheme complacently puts it. Some short distance away, in the very middle of the stream, were some thirty men busily engaged, on a large trestle-built sort of platform, boring the rock ready for blasting; many were at work standing in the water, which was so shallow as not to reach above their waists. After a short run out into the rolling sea from the head of the breakwater in course of construction, we paid a visit to a large dredger at work close by, from whose decks a very good impression could be obtained of what was being done all round, and the length of time necessary to accomplish what was planned out. The north breakwater, which was by far the most advanced, would not, I was informed, be completed for a long time to come. The rate of progress, which is about five feet per diem, was considered fairly satisfactory; at the time of our visit only about half of its proposed length of 2950 feet was completed, whilst the southern arm, which will extend some 2830 feet, was barely commenced. Of course all the works are regulated by the funds at the command of the Colony, and so cannot be proceeded with at any very great rate. The entire cost of the undertaking is to be ?800,000, for which sum the estimate provides 6900 feet of good wharfage accommodation in a land-locked harbour, the entrance to which is to be 600 feet wide and thirty feet deep at low tide, and the two rubble breakwaters above mentioned. Whether or no the harbour when complete will be as eagerly resorted to by "the largest ocean-going steamers," remains of course to be seen. From what I gathered, however, from the captain of the Oceana, there is no love felt among seafaring men for this reef-encircled western coast; they say no matter how much Freemantle itself may be improved as a harbour, the outlying patches of rock will, however well-lighted, always present risks from which the entrance to the natural harbour of King George's Sound is free. The Colonial Government are evidently determined to upset all these old-fashioned ideas, and have made up their minds at any hazard to have their chief seaport within easy distance of their metropolis. The intention is good, and the result will prove its efficiency. What struck me chiefly as being against the success of the undertaking, looking at it purely from an "outsider's" point of view, was the fact that in planning the harbour the engineer had not sufficiently taken into account the ever increasing dimensions of the modern steamships, and that when Freemantle Harbour has been finished, it will be found almost impossible for a big ship to be turned round in it with any degree of safety, unless it has the whole place to itself. This, to my mind, is a very serious obstacle to the ultimate success of the scheme.

THE DREDGER BROUGHT OUT FROM ENGLAND, FREEMANTLE HARBOUR

WORKS.

The sun was low in the horizon when we made our way back after our interesting excursion, and as we steamed swiftly up the quiet reaches of the broad river I could not help pondering on all I had seen, and wondering if ever this now so quiet and deserted watercourse would become the animated highway the Colony so fondly hoped it would, and whether Freemantle would ever be the port of Australia. We stopped at a charming little riverside resort called "Osborne," where, at the well-appointed hotel, I was accorded a banquet by the Press of Western Australia, and which would have done honour to even a London chef. Some fifty covers were laid. Speeches and toasts of the most cordial nature followed, and the friendship and good fellowship which was evinced towards me, a wandering brother journalist from the old country, will remain in my memory as one of the pleasantest episodes of my visit to Perth.

ARRIVAL OF A TRAIN FROM PERTH AT SOUTHERN

CROSS.

The Railway journey from Perth to Southern Cross—Scene at the railway station—Arrival at Southern Cross—The mail coach—The coach journey to Coolgardie—Traffic and caravans en route—Water supply in the Australian Bush—Post stations—A night in a bush inn—The gold escort from Coolgardie—Police in Australia—"Spielers" or blackguards—A roadside letter-box—Exciting race into Coolgardie.

The journey from Perth to the goldfields of Coolgardie, a distance of 450 miles, occupies forty-eight hours, of which sixteen hours are spent in the railway, which at the time of my visit only reached as far as a place called Southern Cross, and the remainder of the time was spent in one of the ramshackle vehicles dignified in Australia with the name of "coach," and which perform the 120 miles in of road through the bush to the now famous mining township. The railway was then being rapidly pushed forward northward from its terminus in obedience to the exigencies of the increasing traffic to the various goldfields, and before this book goes to press the whole of the extension to Coolgardie will be complete, and the coach road through the interminable wilderness of bush and scrub will be a thing of the past, and without a single regret on account of its disappearance, except of course on the part of the coach proprietors, who have naturally been reaping a golden harvest pending the advent of the iron horse.

My preparations for this part of the journey were soon completed, as I learnt that the portion on which I was now about to enter practically meant saying good-bye for the time to civilisation. So I decided to reduce my baggage as much as was compatible with the few necessaries I should absolutely require when roughing it in the bush. A small selection of my commonest clothes, consisting of riding breeches, Norfolk jacket, leggings, flannel shirts, and sleeping suits, and my heaviest boots, made up the sum total of my wardrobe; all such links with civilisation as white shirts, collars, dress clothes, and so forth, being ruthlessly left behind to await my return after the arduous journey. This kit, together with a possum rug (which I had been strongly advised to buy as a protection against the cold of the night in the bush), my tent, cooking apparatus—both of which I found superfluous and were soon discarded—and a plentiful supply of tinned provisions and Bouillon Fleet, made up all that I learnt was necessary for the rough journey I had before me. I was astonished to find that preserved provisions, besides presenting more palatable varieties, were cheaper in Perth than I could have brought them out from London, coming as they do from the other colonies. It is surprising how little is known in England of what can be obtained out there.

The train which I left by was crowded to its utmost, and the scene the platform presented before its departure was a most extraordinary one. It would be a difficult matter to give any adequate idea of the motley crowd I saw around me—all evidently attracted to Western Australia by the possible chance of making a fortune. Every nation on the earth appeared to be represented—Frenchmen, Germans, Italians, Englishmen, Greeks, Russians, all rubbing shoulders together; and all classes, from the wealthy speculator to the broken-down clerk; whilst many a sunburnt miner from the other colonies helped to make up as incongruous a lot of fellow-passengers as it has ever been my lot to travel with.

The railway journey is a fairly comfortable though a long one; a good supper at one of the stations, where a stoppage of an hour for that purpose is made, and a good stiff glass of hot grog before one turns in and rolls oneself up in one's rugs, makes one sleep through the night, cold though it may be, as soundly as though in an hotel.

Southern Cross, which we reached in the early hours of the morning, presented a very bleak and uninviting appearance, being nothing more than a big conglomeration of corrugated iron huts clustered round the base of a rocky hill, on the top of which the bare timbers of a mine shaft were outlined clear and sharp against the pale pure blue of the morning sky. There were no signs of vegetation anywhere, the ground for miles round having been completely denuded of all timber for firewood and mining purposes, when the first rush for the goldfields reached here, some years ago. It would have been impossible to imagine a more bleak and dreary scene than met my gaze on this the first stage of my journey, coming as it did so suddenly after the comfortable quarters I had just been enjoying. There was no time however to be lost in idle regrets, for the coach started in half-an-hour's time, and some breakfast had to be got before starting, as there was no other chance of anything to eat till a stage was reached many miles further on. I found a small inn where I got a rough-and-ready and not over clean sort of meal, to which however I did ample justice, the keen invigorating air having sharpened up my appetite to the necessary keenness to enable me to swallow what I should have turned up my nose at anywhere in England. "Roughing it" is all very well when one has to do it, but "pigging it" is a very different matter, and in this case was really unnecessary, for I learnt afterwards that there was a really good hotel in the place. Although the mail coach was timed to start within half-an-hour I found that there had not been the slightest necessity to hurry, for it was considerably over an hour before even the first horses for it put in an appearance. Meanwhile the mail bags and the baggage had been stowed away in what did duty for the "boot," on the roof, under the seats—anywhere, in fact, where it could be stowed without risk of falling off. Then it came to the turn of the passengers—amongst whom were several women—all of whom numbered several more than the vehicle was constructed to carry; still, as with the baggage, there was no hesitation. In or out they packed as best they could. Many of them made themselves comfortable seats on the baggage on the roof, from which lofty position they had a fine though chilly view of the surrounding country.

The appearance of the uncouth-looking vehicle can be better imagined than described; built on the old-fashioned American lines, it reminded me very forcibly of the celebrated Deadwood coach which was so prominent a feature of Buffalo Bill's entertainment in London a few years ago. Perhaps, if anything, it was more battered and ill-constructed, even to the extent of the wheels preventing the doors from opening; there was no attempt even at sashes, a rough bit of canvas on the sides did service for any screen which might be required against the weather.

I had taken the precaution of booking a box seat some days beforehand, and my annoyance can be therefore imagined to find my seat occupied by a gentleman who had already made himself comfortable for the journey, and who evinced no desire to move. My protests at the office at such treatment, however, were met with such cool indifference on the part of the clerk, and it was so evidently a case of ? prendre ou ? laisser, since the coach by this time was only waiting for me, that I decided that it was useless "getting my back up" when the only result would be my being forced to wait till the next day's coach. So I reconnoitred the situation calmly, and soon discovered that a seat was easily and comfortably improvised on the footboard, the back being formed by the knees of the passengers sitting on the seat above, whilst one's feet hung down over the horses. Not at all a bad position, so long as the latter did not take it into their heads to kick—a very remote contingency from the look of them. Into this novel position I with some difficulty clambered, and, with a cracking of the whip and loud good-byes from the passengers to the bystanders, the lumbering vehicle was started off at the full gallop of its five horses down the rubbly road towards the bush. I was not long in discovering that although I had not got the box seat I had bargained for, I had not in any way lost by it, for my companion, who I afterwards learnt was a Mr. Diamond, one of the most prominent and popular citizens of Freemantle on a short visit to the goldfields, turned out to be as cheery a fellow-traveller and as good a comrade one could wish to meet anywhere. From start to finish his good nature, never-flagging spirits and wonderful stock of anecdotes helped to make the time pass by with wonderful rapidity, and certainly had it not been for him the drive would have been one of trying monotony.

The journey by the "Mail Coach" to Coolgardie is not what might be called a cheap one; ?5 per seat for 120 miles on so ramshackle a conveyance, struck me as representing a fair amount of profit on each passenger. I had besides this to disburse four pounds for overweight of baggage, although I had only brought two very ordinary-sized valises, rugs, etc. (my tent equipment and provisions following by waggon). I learnt that several firms ran conveyances to the fields at much lower rates, but the accommodation they offer is of so doubtful a character, and the way they are horsed is usually so indifferent, as to make the journey considerably longer and even more tedious than by the "Mail Coach." It may be imagined how eagerly the advent of the railway was awaited to put a stop to this "fleecing" on the part of the stablemen, who hitherto had practically had it all their own way.

A very few minutes, at the sharp pace we were travelling, were sufficient to see us clear of the township of Southern Cross and out on to the plain which divides it from the bush, and then I began at once to appreciate the delights of coach travelling in Western Australia. To describe the road we were passing over as bad would be to employ a mild word which did not express one's feelings at the moment. A considerable amount of rain had fallen during the past few days, and the ground was in consequence in that condition which is the worst of any—that between dust and wet mud—a sort of pasty state which made the wheels of the lumbering vehicle bury themselves deeply into the sticky surface; and as added to which, trunks of trees, boulders, and other trifling impedimenta plentifully strewed the track, our first half-hour was a lively one and gave one a good foretaste of what might be in store for us later on. This unpleasant state of affairs fortunately was not of long duration; and though the road was never at any time what we might call even a fairly good one, except in the bush, still at intervals we had, so to speak, to "hold on by our eyelids."

The comfort of the passengers, however, depends to a very great extent on the dexterity of the driver, as I soon found, for if driven carefully the coach can nearly always avoid the deep ruts by going as it were astraddle two sets of them. This is called "quartering," and the middle horse of the three leaders of the team is specially trained to keep always in the rut which is being straddled.

From the botanist's point of view the occasional change in the many varieties of "eucalyptus" gum-trees, which appeared to be confined to certain well-defined zones, or the noticeable absence of the hitherto ever-present "black boy" bush, might perhaps have offered some opportunity for indulging in hypothesis; but to the ordinary observer, once the freshness of novelty worn off, they were to him simply trees, trees, trees as far as the eye could see on all sides; whilst the endless vista of track stretching as straight as a line for miles and miles ahead, hour after hour, has a most depressing effect, which I should imagine is one of the chief results of a sojourn, however brief, in the Australian bush. There are, however, a few distractions which relieved the eye now and again. One thing perhaps which struck me more particularly, was the extraordinary amount of traffic along the whole length of the road, in fact the number of teams we passed during even the first few hours was so exceptional that I remarked as much to the driver, when I learnt to my astonishment that since the big rush to the goldfields, and the consequent establishment of new townships everywhere in the district, business or rather trade has increased to such an enormous extent as to keep in constant employment no less than 700 of these teams, each consisting of a heavy buck-waggon and seven or eight horses. The average time spent on the road is about seven days. All the heavy machinery for the different mines has been carted up in this manner; So when we consider that cartage amounts to ?20 per ton in the winter months, and as high as ?30 to ?35 in the summer, one can realise what it must cost to start a mine and set up a store in these out-of-the-way places; the more especially as in addition to these charges, and the almost prohibitive dues which the West Australian Government consider it necessary to levy on everything without exception which is brought into a country, which, it should be remembered, is still so much in its infancy as to be unable to support itself even to the extent of the ordinary necessaries of life. It seemed to me that fair trade was all very well in an old-established country, but that such drastic measures as these were calculated to keep a new one in a backward state. We passed at different times many flocks of sheep and herds of cattle being driven slowly up towards the fields. Many of these I learnt die by the way; in fact, we were constantly seeing carcases by the side of the road. The animals, in their eagerness for food, often ate poisoned grasses which kill them in a few minutes. This supply of fresh meat is quite a recent innovation, as up till recently the only food procurable was tinned provisions.

Camel caravans were also frequently met with, and, with their swarthy Afghan drivers attired in Eastern costumes, imparted sudden touches of the picturesque which were quite unexpected. These camels, which are largely imported from India, have been used for many years in this Colony and South Australia, and from long use have become quite acclimatised; in fact, it is said that those born and reared in Australia are stronger and healthier than they are in their native country. Afghans, who are also extensively employed out here as drivers, find the climate suit them well, and earn probably ten times as much as they would in their native fastnesses. It is curious how frightened horses out here are of these camels. Not only did ours, on every occasion that we met a caravan, evince strong symptoms of bolting, but even the sight of a camel's pack lying on the ground was sufficient to make them prick up their ears and attempt to shy from it.

Want of water, which has always been the bugbear of the Australian bush, is still looked upon as an exceedingly valuable commodity in these parts, in spite of the dams the Government have been building lately all along this route, though the heavy rains which had fallen previous to our arrival had had the effect, however, of filling them all to overflowing, and so considerably lowering the price per gallon. The greatest drawback to the development of the country has, and will always be, the scarcity of fresh water. All the so-called lakes—which, by the way, in summer are only so in name, when they are merely dry sandy flats—are, when full, composed of a liquid so saturated with brine that sea-water would taste sweet in comparison, and the many borings which have been made all over the bush have, in most cases, only tapped subterranean salt springs. The chief drinking-water in use for some time past has been that obtained by condensing this brine; so the value of it may be imagined. At most of the stations we stopped at were notices up—"Water for sale"—though where the Government had got a reservoir near, the profits arising from the sale of condensed water were considerably lessened; in fact, the proprietor of the condenser has to be content with the same price as is paid at the dam, or shut up shop. I visited one of these huge tanks, and found that although the water was somewhat cloudy in appearance, the taste was that of pure rain-water. The place was about a hundred yards square, and had, I was told, nineteen feet of water in it, which was sold at the following scale of charges, being pumped up, as required, by the caretaker:—

| s. | d. | |

| One hundred gallons | 2 | 6 |

| Fifty gallons | 1 | 6 |

| Less than this, ?d, per gallon. | ||

| Horses, mules, donkeys, cattle, per head | 0 | 2 |

| Sheep, pigs, at per score, per drink | 0 | 4 |

| Camels, per drink | 0 | 4 |

| Foot travellers free. |

Twelve months ago, before these dams were constructed, the hundred gallons cost ?2 10s., or 6d. per gallon—an enormous difference. I was told that in those days the amount horses could drink at 6d. per gallon was simply heartbreaking. Artesian water is being actively sought for everywhere, in spite of the opinion of geologists that no such water will ever be found in the Colony.